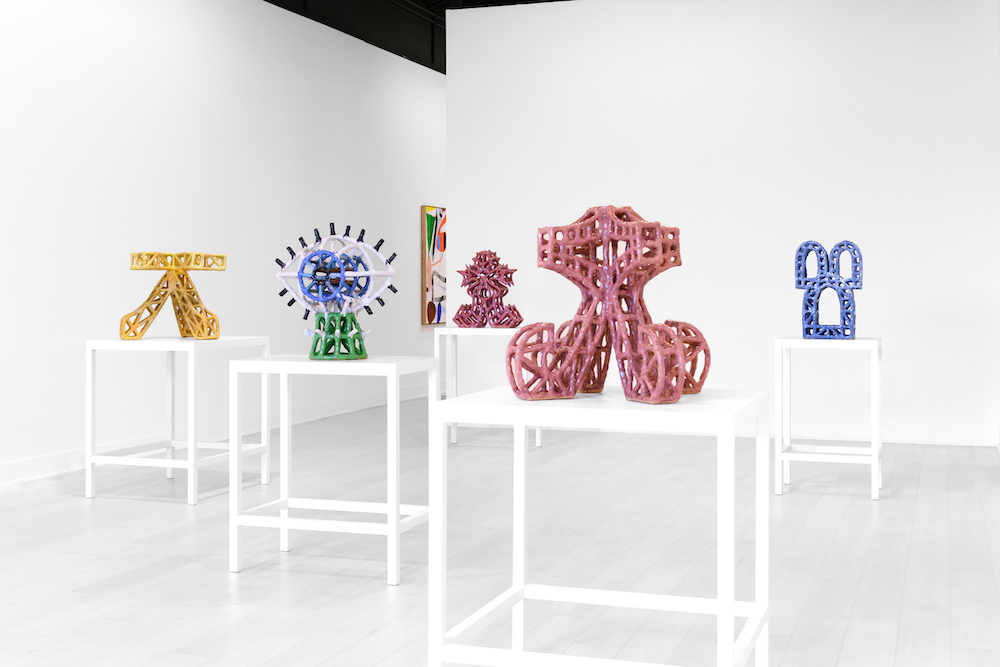

pt. 2 Gallery is excited to present Earth Scraper, an exhibition of new sculptures by Nick Makanna. Makanna works with clay to create his series of freestanding forms, each piece comprised of dimensional linework and deft manipulation of positive and negative space.

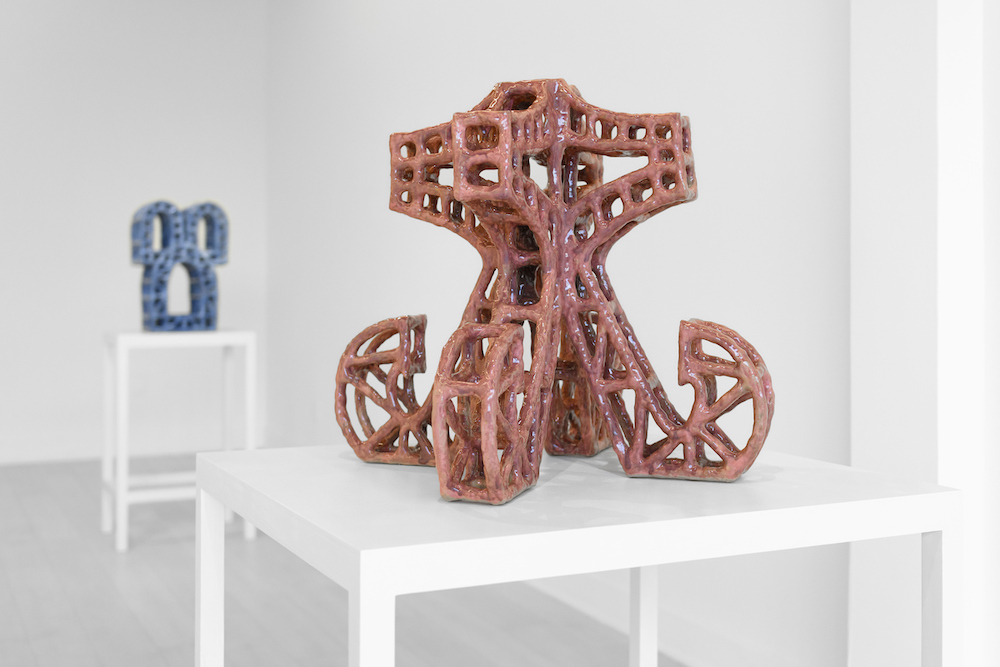

The title of Earth Scraper immediately evokes the physicality of creating the forms — scraping, attaching, adjoining — just as the fingerprinted texture of the work leaves evidence of the artist’s hand. An earth scraper is also the theoretical inverse of a skyscraper, diving into the earth in the same way a skyscraper projects toward the sky. Makanna’s forms straddle this boundary between ascent and descent; they are airy, stilt-like structures built from the mud of the earth.

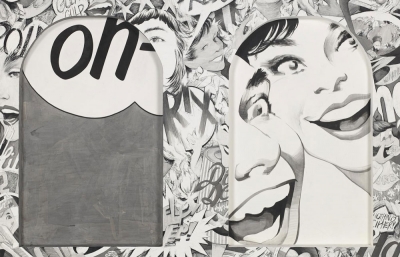

This exhibition is a continuation of Makanna’s Rune series. The term is duplicitous in meaning as it describes these structures’ similarities to pictographs and hieroglyphs, as well as to the homophonic “ruins.” Influences for the Rune series arise from brutalist architecture and industrialism as well as gothic buildings and early Renaissance art. The shapes of Roman aqueducts and Greek amphorae combine with the outward wing-like projections of Spomenik monuments, yielding these almost postmodern creations — referential shapes used to communicate meaning through form.

Makanna deftly merges interior and exterior in these objects as the shapes encased in negative space become as prominent as the forms themselves. He builds dimensionality with repeated 2D facades stacked in sequence. Each piece could be a building in ruins, stripped of its walls, or in the midst of creation, a frame to be built upon. They are foundational structures, supportive and sound, but also carry an innate fragility, an airiness, a sense of levitation. The wings or windmills of many of the forms give an allusion to flight. In Earth Scraper, the push skyward contends with the pull of the earth.

Some of these sculptures are more explicitly figurative; Makanna notes references to the demons of Michaelangelo’s Torment of St. Anthony in the spiky protrusions of one work. But even the architectural structures take on an impish figurative quality. Much like the oil rigs of the Oakland harbor resemble dogs digging on the horizon, or metal towers of transmission lines stand almost humanesque with limb-like extensions, Makanna’s sculptures have a fantastical motion, a coyness, a magic that imbues them with life.

These sculptures, animate in their structure, lie at the intersection of figuration and foundation; earth and sky; stability and fragility; beginning and end. In viewing them, one may be reminded of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, of a passage where a fictionalized Marco Polo is met with structures like Makanna’s:

“Those who arrive at Thekla can see little of the city, beyond the plank fences, the scaffoldings, the metal armatures, the wooden catwalks hanging from ropes or supported by sawhorses, the ladders, the trestles. If you ask, ‘Why is Thekla’s construction taking such a long time?’ ... they answer, ‘So that its destruction cannot begin.’” —Annie Dauber