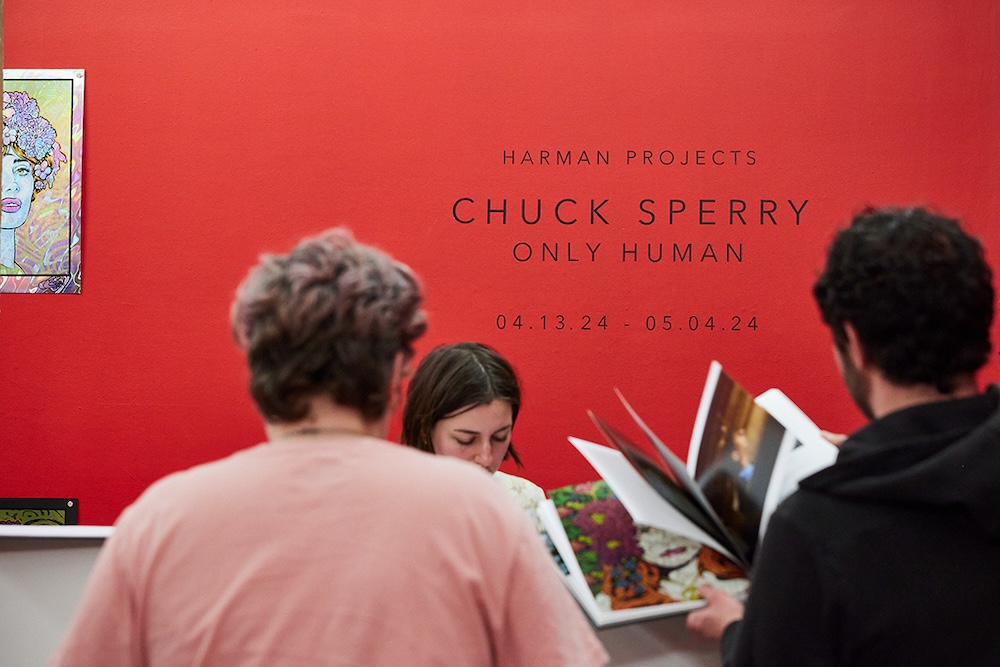

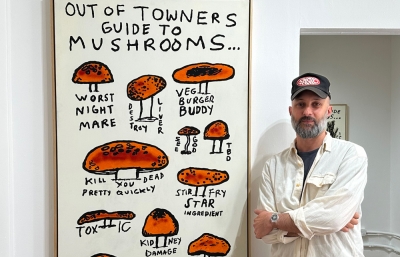

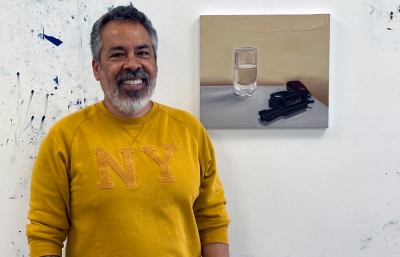

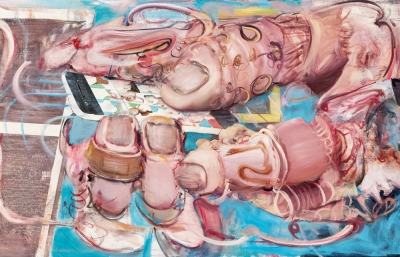

It may surprise those who are familiar with artist Chuck Sperry’s long and multifaceted career that the man is, in fact, just one man. From art shows to key-note speeches to making some of the most iconic rock posters of his time, Sperry’s prolific output seems like the work of many hands—and it is, in a way, as the artist has embraced collaboration his entire career. For Sperry’s latest solo exhibition with Harman Projects in New York City, Only Human, the Oakland-based artist turns inward, inspired by the faults and powers being human can give us.

Before his solo exhibition opened in NYC, Sperry caught up with Harman Projects to discuss his political activism, his muse series, and what he loves about being human.

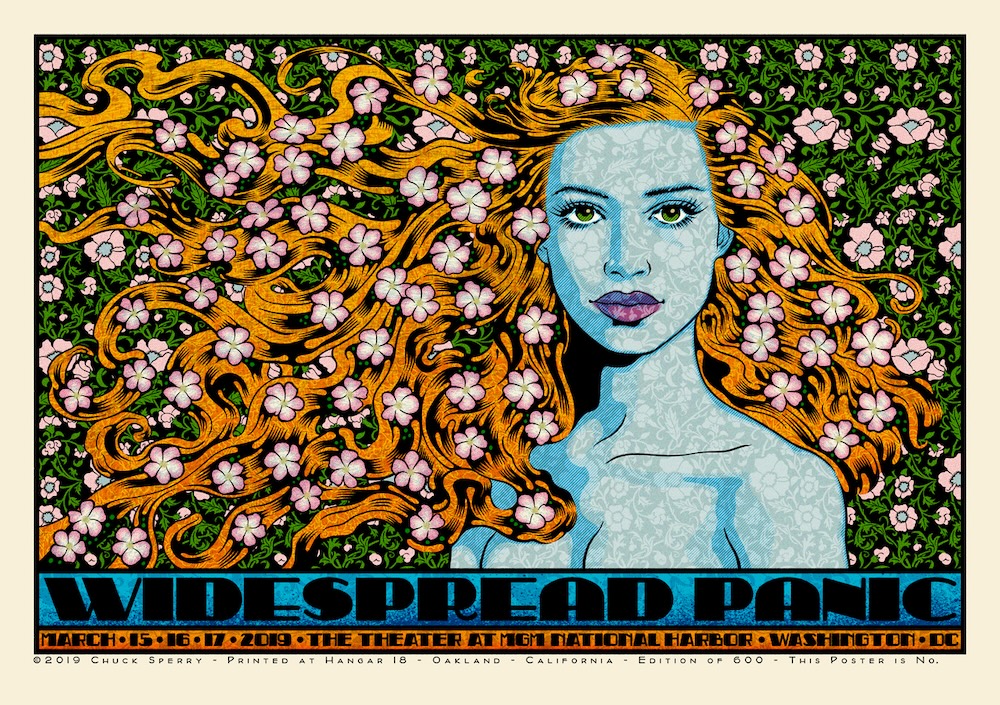

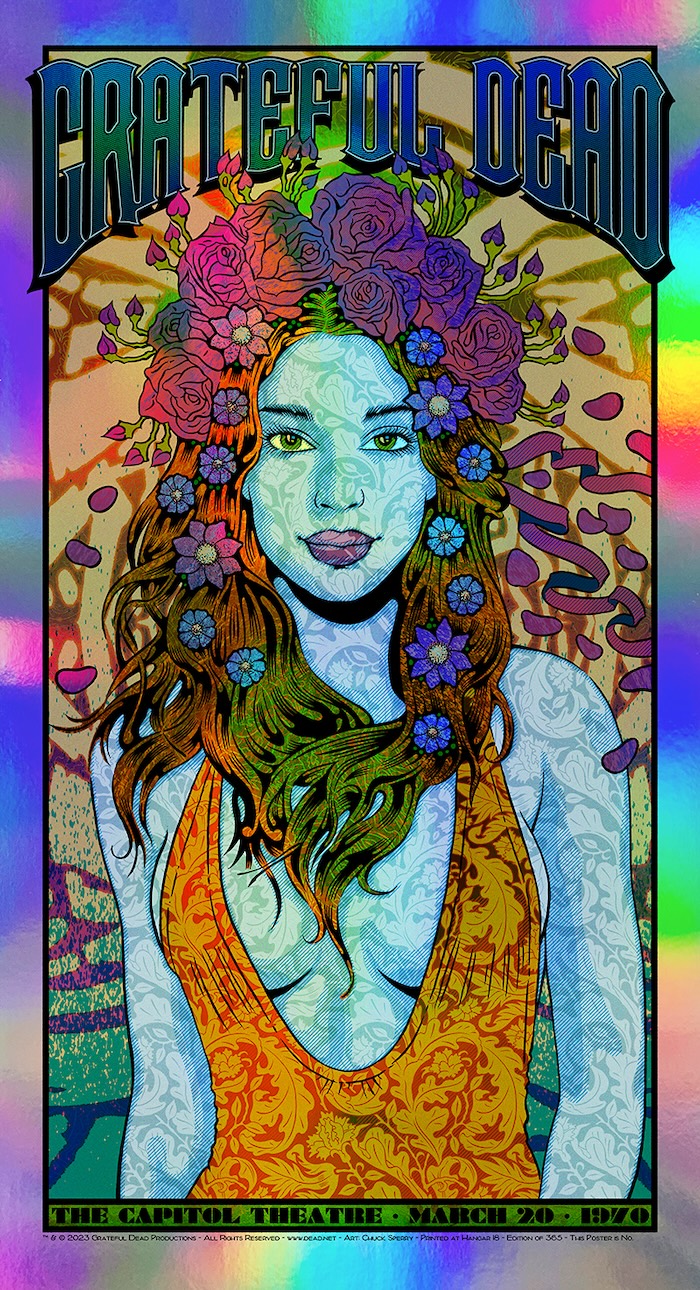

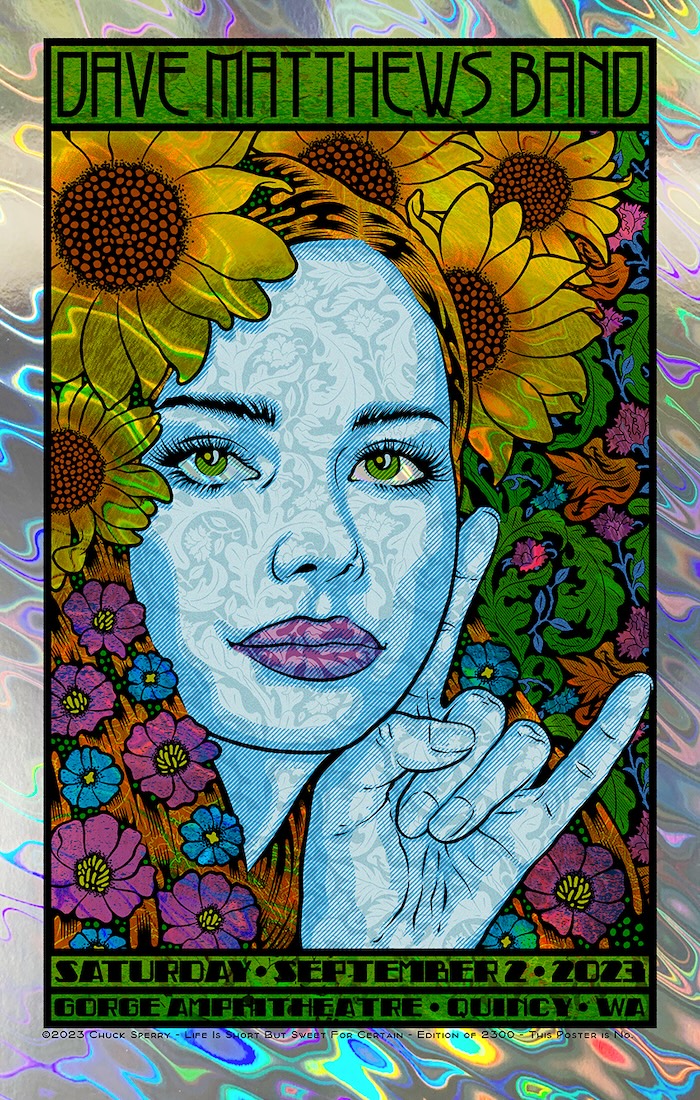

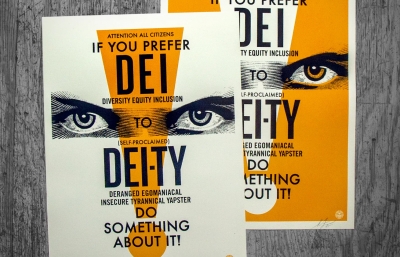

Harman Projects: Chuck, you’re best known for your psychedelic rock music posters, especially the “muses” series—some of which are on view right now at Harman Projects in NYC. I actually want to start by asking you about your more political work. You’ve been involved in many social movements, specifically ones against United States imperialism, emboldening the power of the people. Have you always considered your work to be political, or yourself to be a political artist?

Chuck Sperry: I have always considered my work to be political and accessible. I’ve focused my art to appeal to the broad general public. I make art for regular folks like us; I share my audience’s ideals, aspirations, and goals. My consciousness is that of a working stiff, and I never forget it. It is my hands and labor that brought me here—where I am now. And if I achieve some great or rare accomplishment, I try to do so humbly, remembering everything good comes with hard work.

I also remember you saying you took inspiration from the French Situationist posters of May 1968 demonstrations and fellow Oakland artist Emory Douglas who made work for the Black Panthers from 1967-1980.

I had the distinct honor to work with Emory Douglas on projects and reprints of his classic Black Panther images. He gave me permission to reprint three of his amazing Black Panther Party newspaper designs in large format color screen prints on cotton rag paper as art prints. These were sold at Lazarides in the UK, and at Spoke Art in San Francisco way back when [gallery owner] Ken Harman and I met. I hooked him up with Emory right away.

I “opened” for Emory at a gigantic design conference called Trimarchi in Mar del Plata (near Buenos Aires) Argentina. Our powerpoint lectures were in a basketball stadium. The place held 5000-6000 people in the audience. It took a fair amount of willpower for me to take the stage in front of that many people. At any rate, my lecture covered the history of concert posters and counter-culture that led from the psychedelic sixties to the present. After me, Emory headlined, starting off with a resounding: “Power to the People!” His lecture was very inspiring and brought many to tears.

Emory is the real deal. Me, I’m more in the entertainment space. But building the bridge between those two worlds—activism and entertainment—serves a function. I love to do that.

A few years ago I met Alexandre D’Huy, a French artist who invited me to the École National Supérieure des Beaux-arts in Paris to print a punk rock poster I designed for a French group called Operation S. The studio I printed in was the Atelier Populaire where Guy Debord and the Situationiste collective printed all their classic activist posters during the student strike in solidarity with the unions in May 1968. I used the same press! A perfect mix of music and activism on hallowed ground.

What an experience! It seems the music culture you often made posters for was never totally disconnected from these political movements.

I don’t really see any difference between politics and music. When a singer brings everyone together and makes their heart sing as one, it is a political act. To do so for the right cause is excellent, even better. For instance, the Power to the Peaceful events in Golden Gate Park organized by Michael Franti was a great melding of music and politics. Michael brought thousands of people out to Golden Gate Park to see a show, and invited all sorts of political action groups to the event to educate everybody. The Power to the Peaceful shows were quintessentially San Francisco at its finest.

Speaking of music, your work will be featured in the SFMOMA exhibition Art of Noise, an expansive museum exhibition examining music-centered design in San Francisco’s booming era of counterculture in the 1960s and 1970s. You and your work were instrumental in creating the visual culture of an entire era defined by music and gathering.

I’m incredibly grateful to be included in the Art of Noise exhibition at SFMOMA, which will run May 4 to August 18, 2024. With Art of Noise I’ll have a selection of my concert posters enter the permanent collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. It’s a dream come true! Many thanks to museum curator Joseph Becker, who took time to discuss the exhibition at length, make a visit to my studio in Oakland, and refine the print selections to very solid pieces to be shown and permanently collected. I bet you’re dying to know which ones. I’ll leave that as a surprise for those who support the museum and buy tickets to the event. It will knock your socks off, and I’m in great company.

When you look back at your career, what are three moments—maybe forks in the road—that pushed you into the career you’ve had?

I would put moving to New York City high on the list as an important juncture. I lived on the Lower East Side right in the wake of the Art Boom of the 1980s. There, I met Seth Tobocman and Peter Kuper and all the editors of World War 3 Illustrated, America’s longest running political comic book. Those encounters brought me into contact with so many legends and luminaries, both artistic and political. Living in New York City as a fledgling artist made me reach higher, run faster.

Moving out of New York City and relocating to San Francisco was the smartest thing I ever did. I formed an artistic game plan in San Francisco: I took up with all the underground cartoonist legends of the West Coast; I started printing screen prints with Ron Donovan and Orion Landau. Together, we formed a print studio called Psychic Sparkplug, making posters for great bands at great clubs: Trocadero, Slims, Covered Wagon, Golden West (Albuquerque, NM) and Jabberjaw (Los Angeles, CA). We made a bunch of rowdy screen printed posters for amazing music in short order. It was a blast! We used to regularly bowl with Frank Kozik and a number of rock bands and record label folks. The San Francisco scene blenderized art and music with a dash of booze.

Striking off on my own, being a solo act so to speak, was perhaps my third “fork” moment. Being able to call my own shots really made my decisions more rational and straightforward. By doing that, I was able to forge my own associations with galleries, musicians, and other artists, and to collaborate effectively. I met Ken Harman during this time. His support and guidance has brought my art to amazing heights. Meanwhile, it has been up to me to raise my game, dig in deeper to my subject matter, and fill out the details of my artistic vision.

On the road to discovering the dimensions of my artistic vision, I produced three art books: Helikon, Chthoneon, and Idyllion—and one gigantic 752 page poster book that covers my entire artistic path: Color x Color: The Sperry Poster Archive 1980-2020. Seeing where I’ve been helps me to plot out the next fork in the road.

I want to ask about your influences. I read somewhere that you align your poster works with the styles of artists from the Vienna Secession and Art Nouveau movements. How do you feel these movements intersect with Psychedelic art?

The Vienna Secession and Art Nouveau brought art out of elitist settings, moving art and art objects into peoples’ lives. It was a part of the beginning of the process of democratization in the arts. Industrial arts and crafts were brought into the artistic sphere, and could be used as artistic mediums to express oneself. These ideas were consciously re-evaluated by the radical artists and social experimenters of the 1960s, like [music promoter] Chet Helms. Helms deeply appreciated Art Nouveau and its populist power, and through his aesthetic interests opened artists to create psychedelic poster art of the 1960’s.

These same democratic threads of thinking and social movement appear to me to have most recently expressed itself through Urban art. I love that my work is often categorized as contemporary Urban art, although usually I resist categories and prefer instead to keep working towards my own star.

You’ve been working through the Muse theme for quite some time. What refreshes your interest in it through each design?

I am a very stubborn person, to be honest, so that’s one reason I’ve stuck to this theme. When I started I never thought it was possible to make so much headway into such vast territory. The theme is incredibly rich, the territory is vast. Technically, I find refinements, new color combinations and printing techniques I can make in the next piece, each time I make one.

It’s a circle, like a bar of improvisational music that returns to the top richer and more focused. And that is why I stay with it. It brings me so much discovery, always! I’ve found that my dealing with mythological material for so long, and keeping much of it loosely structured around the Orphic Hymns, I’ve discovered a lot about myself through it. It brought me a lot of personal insight that has changed my life for the better.

You’ve also mentioned that as you’ve done this series, you’ve gone deeper and deeper into Greek Mythology. Has this influence been applied in non-Muse works? Or are you being strict with yourself and keeping it to this single series?

The ancient beliefs are pretty much pervasive in my life and art, and it has spilled over into every sphere. Strict? No, I am drawn towards freedom, not stricture. I try to remember that freedom brings its own responsibilities and concerns. For instance: I bought a house in the South of France in 2019. Bold, free move, right? But it's a house [laughs] so that freedom comes with house-sized responsibilities. I like to say I “adult” in two languages.

Okay, but here’s the influenced-by-myths part. It’s in the South of France, which has Greek and Roman ruins everywhere. There’s a footpath behind the place that has to be ancient. The woods hold a mystery as though there are dryads and nymphs living there. Now, I grow and tend olives. There’s laurel and grapevines and figs. In a way, I’m living inside those ancient stories on the Mediterranean and pulled into those rhythms of life, which I only used to read about.

At any rate, myths are pretty blurry stories to begin with. They all have various tellings. Different versions come from regional or historical differences. Some versions are an amalgam of cultures. Isn’t that complexity so recognizably contemporary in respect to truth? The more you bear down on the facts, the more elusive reality becomes. It’s very quantum or fractal disposition. I find more and more that I am certain of less and less. That said, I always focus on the progressive and contemporary resonances in these stories, and think there is much of value to contemporary thinkers in progressive movements.

Have you noticed any narrative or stylistic arcs looking back at your career? I.e. where you’ve been versus where you’ve landed?

Long ago I was obsessed with trash culture. The arc has been to shift my attention towards more universal themes. I’m concerned with the collective unconscious and its expression and projection into the rituals of daily life or into the appearance of things. My earlier interest in trash culture was an interest in its relationship to those unconscious archetypes. Now, I like to imagine those archetypes in and of themselves. Archetypes are projected upon my mind in human form, I suppose, because I’m only human.

I know you’ve experimented with other mediums through your long career, but often returning to silk screen. After all these years, why have you stuck with screen printing over other printing mediums?

I’m excited by screen printing! It’s a joy to go to work. My studio is a big playground full of all the toys it has taken a lifetime to gather. Photographically exposing screens from film is a magical chemical and physical process. Printing and layering and mixing inks is alchemy at its finest. Using my hands. Interfacing with the paper and the result of layering the inks. All of it is sweet music. I’m a very lucky artist. I’m forever grateful to have this life dedicated to making beautiful things and sharing beautiful ideas with people.

What inspired the title of your latest exhibition with Harman Projects, Only Human?

I was inspired by an acknowledgement of my limitations—that I’m only human, mortal and fallible. Only Human refers to my commitment to craft and manual art production in tangible media. The idea behind Only Human is to show the way forward in the 21st Century: that art made by humans for humans in physical reality is imbued with the soul of our humanity, our uniquely mortal heart and immortal spirit, drawn from our human culture. Our human collective unconscious and experience will transcend the current imperative for non-human and virtual intervention in the art space.

Such art delights the gods, and perhaps will delight you too. I hope so.

Only Human is on view through Saturday, May 4th at Harman Projects, 210 Rivington Street New York, NY. Studio portraits by Shaun Roberts.