Sitting in a shady public park under a verdant canopy of hundred-year-old trees as Wimbledon plays on a giant screen, this visitor feels like a lucky extra in a novel or movie situated in London tradition, and the Woolfian setting steeps into you like a proper cup of tea. The moment finally arrived after a 10-day quarantine and pent-up anticipation of the surrounding scenarios, my only interaction with the outside world being trips to the mailbox to send the mandatory tests, this in a metropolis frenzied with energy. England was in the Euro Cup final, which felt like the Super Bowl x100, and Boris Johnson had just declared July 19 as the re-opening of the nation, a “Freedom Day,” as they put it. I had finally arrived in what I perceived as London, a film set of an old place, watching a prestigious 144 year-old tennis tournament where the players perform in compulsory, pristine white and the audience, sprinkled with Princes and Princesses, sport elaborate hats. It’s all so staid, a bit regal, this annual celebration since 1877, which inevitably sparks a sense of irony, or in my case, a sense of anxiety: this sort simple observation of traditions that persist amid an incredible wave of the unknown, our past “normal” lives colliding with a new existence of Covid tracing, travel restrictions, Delta variants, social distancing. The off-kilter nature of the moment is palpable once experiencing something previously considered normal.

The circumstance that brought me to London was one of loss. Even in that universal event, a moment we all face, the world has been so turned upside down that we are forced to rethink relationships as the things we treasure. We are programmed to believe that the world will accept our tragedies, our grieving, and act accordingly to a normal set of rules. First off, that is no longer allowed. We accede to quarantine, accept this new way of being from the get-go, and automatically adjust to travel in this new pandemic world. Everything you used to do normally is not available, even in an event of unforeseen loss. For a culture writer for whom art is a love, a distraction and a routine, who found travel as a vehicle to elicit a bit of an escapist fantasy, I’m now in London a bit unexpectedly, attempting to establish rhythms from a previous life. And that fantasy part of a previous life is no longer needed.

Because art has always been a constant, for generations, sustaining and guiding many of us through difficult times. We memorialize tragic and epic events through art, play a favorite song when we are sad, watch a film when we need to be distracted, or go to our favorite museums when we need some tranquility. The pandemic has certainly taught us that we need these things more than ever. As we transition into a new way of life, these routines that ground us, embrace our shared humanity, seem to have been snatched during the pandemic. In London, at this present moment, in trying to re-establish that overwhelming sense of beauty and need for art in my own life, I was also trying to come to understand what it is we lost. And really, I spent most of my time looking at how it is that art is a tool for understanding transitions in life, to explain grief, to capture the unexplainable. So, in this fractured moment, with London’s historical convergence of centuries of art and history, of pageantry and uber-contemporality, of just simply old world versus new world, it was the perfect place to be.

Hackney and East London

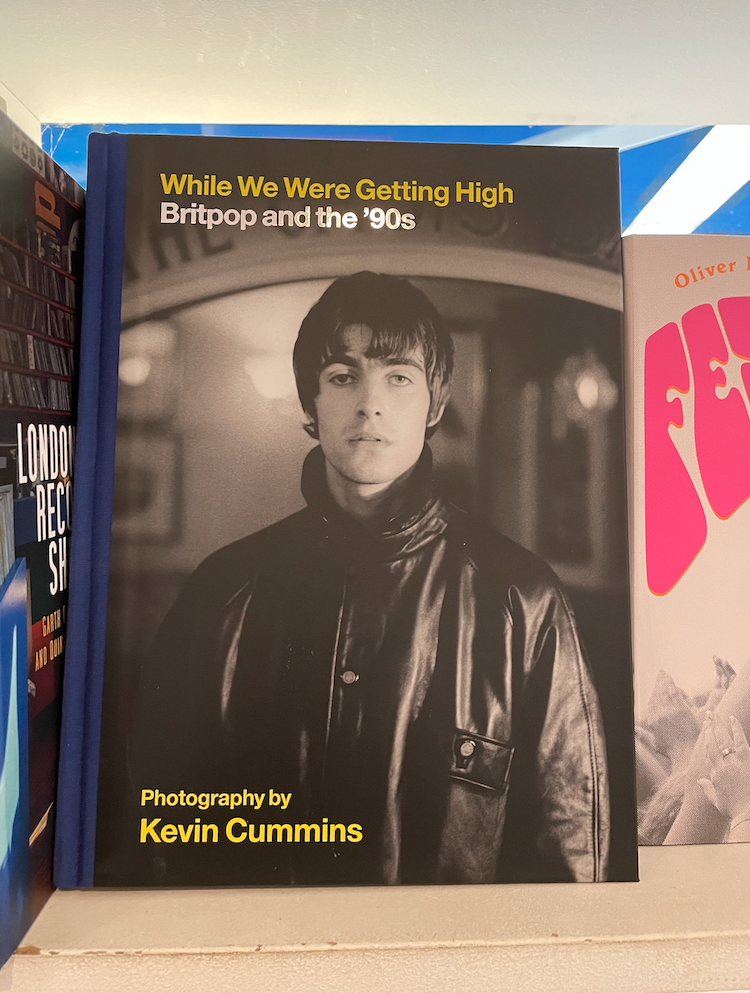

This is where my first 10 days were spent, and multiple stretches thereafter. I was desperate for a routine because the arrangement to travel to the UK was the antithesis of a normal schedule. I was staying near London Fields, which I vaguely recognized from the Martin Amis novel. It proved to be a really essential part of my trip, the gateway to everything I would do in my first few weeks. Broadway Market is sort of a hub, and I found myself there for morning coffee, afternoon coffee, and preceding evening coffee, pint or meal. Pavilion also has great coffee and bread, as does Climpson and Sons. I spent a lot of time in bookshops, and this being London, literary appreciation is quite ingrained. Artwords and Donlon Books were my mainstays, the latter boasting a fantastic collection of zines and rare books, which made for multiple stops and multiple purchases. (I ended up with Joan Didion short stories, the irony of missing home.)

But it was summer, and the center of the action was London Fields itself, and along the paths of the canal that cuts through Hackney, I spent time in Victoria Park, which had a few nice public art pieces, including two great sculptures by Romanian artist, Erno Bartha. There was a sense of calm and peace in the Park each day, and access to coffee everywhere. So, naturally, I spent a week at the Bethnal Green Town Hall to situate myself even longer. Having spent previous London visits mostly in the West, this was the first opportunity I had to explore this area of East London. Again, seeing that the country was still on lockdown and tourism at a bare minimum, being situated in a more residential section of the city was the best plan. Maybe this was a sense of calm that was needed. I was adapting to what was allowed.

Art All Around

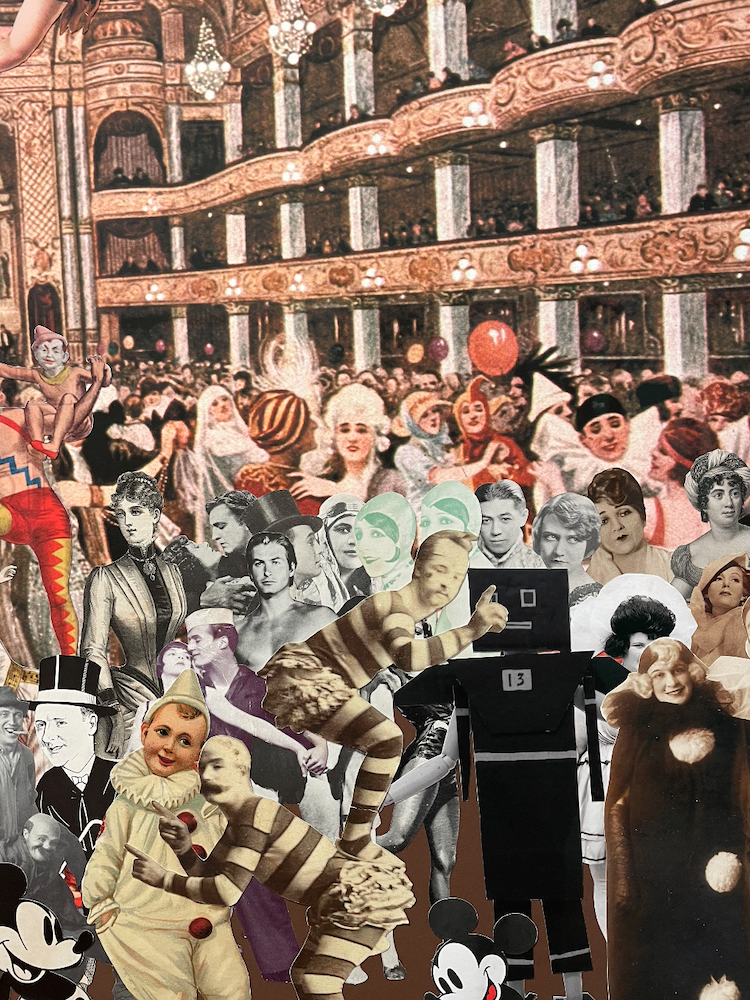

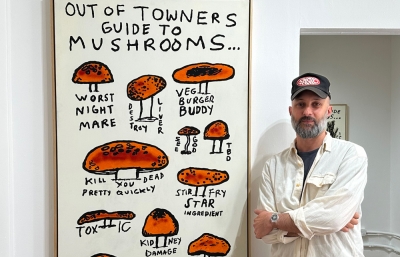

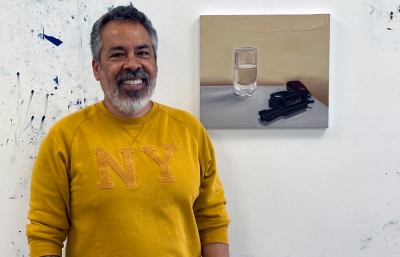

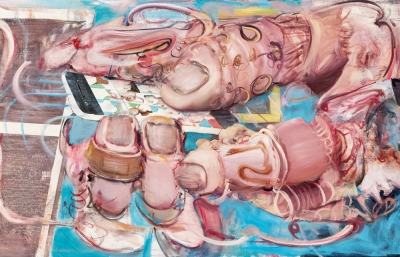

So, within all this, there is art to see, and that was the routine I really wanted to re-establish: seeing art for real. London may be the best institutional art city in the world. There are museums everywhere, old world collections in unique buildings and galleries in every neighborhood. Of course, I made the usual stops, regardless of mask mandates and reserved viewing. Matthew Barney’s Redoubt film and installation was on view at Hayward Gallery, alongside a fantastic installation of works by South African artist Igshaan Adams that could have been overshadowed by the grandeur of a Barney film (it was not). In the brutalist architecture of that building, as well as the Barbican’s literal hard-edged splendor, you are also visiting the structures themselves. In more central London, I made sure to check in at Carl Kostyál’s space on Savile Row, which was hosting a new series of works by American painter, Rebecca Ness. Saatchi Yates has a grand showroom for art, and Waddington Custot had a great Peter Blake collage show. There are plenty of galleries on the two blocks around Savile Row, making it quite easy to do a full-on gallery day. Muzae Sesay had a great exhibition at Public Gallery, an emerging space that we all keep our eyes on. I also love the Royal Academy, and there was a brilliant (as always), David Hockney show, The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020, extended for the fall. How exceptionally timed, too, for the experiences I was having: a major exhibition about rebirth after loss, about nature, painted on an iPad. This physicality and growth in the natural world synthesized through technology, turned into something so breathtaking. Nature has a routine, and we humans adapt to it the best we can.

I went to two collections that I had never seen before on the recommendation of a friend. There was a definite comfort in viewing the most ultimate of old world staples. The first stop was the Wallace Collection in Marylebone, occupying Hertford House in Manchester Square. It’s a massive townhouse with floor-to-ceiling displays of paintings, sculptures, and armour, in the setting of what almost looks like a movie set. Sir Richard Wallace built the collection in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, with work that spans the fifteenth through nineteenth centuries. After focusing on contemporary art during this trip, it was a welcome respite. On display was an incredible presentation of two massive Rubens, the first time in 200 years that The Rainbow Landscape and A View of Het Steen in the Early Morning had been exhibited together. The second stop I made was to Sir John Soane’s Museum, the home and library of nineteenth-century architect Sir John Soane. Just as dense as the Wallace Collection, this equally incredible building held unique spaces, hidden rooms, grand ceilings; a true gem of both architecture and the art of collecting.

I haven’t mentioned coffee in a couple of paragraphs, but what is a trip to central London without a stop at Monmouth Coffee in Seven Dials? As a connoisseur of the fine effects of caffeine, there is little else in the world better than Monmouth. Just down the road in Soho, there is the famous and venerable Algerian Coffee Store, established in 1887. As this theme emerged constantly on this trip, I set things up in these dichotomies of what is now and what always was, testing it for vulnerabilities. But these old staples remind you that even over 100 years ago, there were people establishing their own routines that have stood the test of time.

Ruskin’s View and Leaving the Metropolis

London is its own self-contained universe, a nation with a nation, but there was much to be seen outside the city. After a year’s delay, The Vanguard show at the newly reopened Bristol Museum documents the unique history of counterculture in the harbor city. In the Brutalist “oasis” of Basildon, one of the country’s “New Town” developments in the 1940s that literally was created as a self-contained suburb, a street art program called “Our Town,” produced by Re-FRAMED productions, just kicked off. As the city infrastructure of Basildon itself was created with the advice of artists and architects working together to form a unique and new urban experience, the Our Town curation is an ode to the city’s original intent to connect the arts and city-planning.

I wanted to get away for a few days, and one of the places I decided to stay was the town in Northwest England of Kirkby Lonsdale in the north, famous for what is called the Ruskin’s View, named for John Ruskin, a prominent art critic and painter of the Victorian era. JMW Turner painted the view in 1822, and, indeed, it does look like a painting as you peer from a church cemetery above. There was something so raw about this view, this sort of counterpoint to my whole trip. I had read something so great about Ruskin that, obviously, made me want to go to this town: “In Ruskin's repudiation of everything modern, we detect that fine dissatisfaction with the age which is perhaps only proof of its idealistic trend… there existed in him, side by side with his consuming love of the beautiful, a rigorous Puritanism.” How supremely apt in the current state of things. We are thrust, and I use that word again, into this contemporary landscape, a world of Covid testing, tracing, or family tragedy, watching nature battle with humanity, and you are sitting on a hill overlooking a view immortalized 200 years before, realizing how unsettling this experience really is. There is anxiety in this new balance between old and new, and at times, it seems so obvious as we cling to past world examples of what art is and can be. If we were ever in a transitional phase, our current moment has established our need for a sense of what the world used to be. And here is Ruskin, probably doing the exact same thing two centuries prior. Looking for purity, or enlightenment instead of what is in front of us.

That purity and sense of value in the arts, of how we experience the things that we love, are more vital than ever. That preserved view of rolling hills, now two centuries old, helped me understand how incredibly intricate tradition is in making our contemporary lives, a sense of comfort in the face of collective unease that is beyond palpable. It is essential. —Evan Pricco

A personal thank you to the lovely staff of the Zetter Townhouse in Marylebone for their generosity and incredible bar and dining room.