Patrick Martinez

The Neon Landscape

Interview by Evan Pricco // Portrait by Brian Cross B+

On a warm and sunny December morning I drove across LA, from the west side to Huntington Park, specifically, to see Patrck Martinez in his studio. The sprawl is palpable, throbbing with the nuance of a city that blends and expands under a particular sunlight that is quintessentially Los Angeles, making my drive the ideal start for an interview with an artist who creates work about specificity. Martinez has taken the landscape of LA, a place he characterizes as still “in-progress,” making work that combines mediums, styles, eras, cultures, neighborhoods and the unique characteristics of his panoramic view.

We spoke on the occasion of some major acquisitions of his works, notably by the Whitney Museum, but also because of the rising tide of brilliant talent coming from Los Angeles over the last few decades, led, incidentally, by the likes of Patrick Martinez. The neon sign works are perhaps his calling cards, but the Pee-Chee folder paintings and landscapes are signature as well. We spoke a lot about LA in this interview, but also about the changes in his personal life, what he learned from graffiti and how to resurrect that youthful honesty in his works.

Evan Pricco: LA is ingrained in so many peoples' heads as a certain kind of place. Even if someone's never been to LA, there's the aesthetic of Los Angeles as an idea and not just a place. I think your work perfectly embodies that.

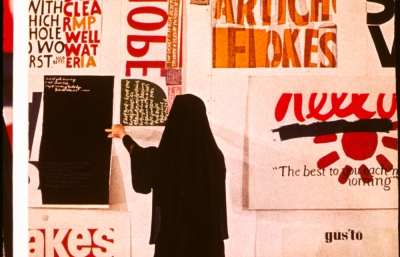

Patrick Martinez: I guess I'm tapping into the land, right? That's my whole idea with these pieces that I'm making with the stucco, the neon, the tile and all that, taking materials from the land to create the landscape. Sampling those sections. That specific orientation, or the way I'm composing it, is specific to LA.

I was thinking about your neons, like the way that you put those words together. It does feel very California. Even though the words hold individual meaning, there still seems to be something very, very southern California about even the phrasing.

Yeah, the sourcing. I'll take the words and really speak to the passerby in LA. That's how it started. I'm driving down Woodward Boulevard at night, and I'm noticing all these signs, and it's one of those things where it feels like the city is speaking back to me. It's a weird thing because, in LA, everyone talks about the traffic and everything being congested, but at night it feels kind of desolate. These neon signs are on and the stores aren't open, yet the messaging says “come here, we do this, we do that.” Right? I'm thinking that if the city's speaking to me, what would it be saying and what would the passerby be saying? If I took what the passerby was saying and put it into the neon sign, what would that be?

Some of the phrasing is specific to LA, and some of the icons and the vocabulary that I sample are from what the land provides. I'm thinking about different places that I've seen and the people who are here. For example, El Salvadorian restaurants and how they use palm trees in their neon signs to sort of speak about being from a tropical place. How could I use that palm tree that already exists and use it in a bioscape in my painting? Because I'm always thinking about how I can build a landscape with the materials that already exist. So, palm trees, obviously, exist in LA, and I'm trying to find the connection between existing vocabulary that is both from here and about coming here. Then it's loaded, right? Because we're talking about people who are coming here from different paradises to their idea of paradise—or what they thought of a paradise that is Los Angeles.

LA is perceived as paradise for so many people.

Yeah, and that's a hard thing. LA is one of the most expensive places in the world to live in, but you're always working and trying to obtain this sublime ideal.

Well, no doubt, the dream is expensive, but let’s get back to this idea of LA going quiet at night. That's such an interesting thing you are saying about the neon. It’s like a brightness among this quiet emptiness. New York, it's vibrant at night and, for me, LA feels more vibrant during the day.

It is and it's a lot of land to cover. And it's left to right. New York, I feel it's an up and down orientation. That's why a lot of my pieces are left to right.

Oh, I like that, let’s stay here!

For me, I feel like LA is left to right; you're always driving in your car, and you're always looking in an orientation that is kind of cinematic, like watching a big movie screen. In New York, I feel like everyone's looking up. A lot of people don't drive in New York; they always seem to be on foot. For LA, it does feel like this kind of dark place at night, and it can feel kind of desolate at times. It's so congested in the day, and certain areas are harder to get to in the day, but at night, you can get to your destination in 15 minutes.

This constant panorama is what I was thinking about just now. The sprawl feels really, really intense at night. Because you're actually not going that far. I guess it kind of speaks to the idea, too, of how you collage things together. When you observe and pay attention, LA feels like a place where collage elements just emerge from the city itself.

In some of the work I'm investigating now with central Mexican murals, the style that I actually sample for the paintings was their collage of styles. There’s a hybridity in style which naturally arrived and translates into Los Angeles. The same type of Mayan images could also exist on both surfaces in LA. There's also an amalgam in play. I'm from a mixed background. My dad is Native American and Mexican, my mother Filipino, so that hybridity is something that I try to work out in the pieces.

Also, I think people can kind of relate to that. Even if they're not from a mixed background, I think they can understand how dynamic the city is in terms of people actually coming together and knowing that their cousin or their brother married someone from a different place, you know what I mean? They understand that it's not separated in that way. The hybridity is what I'm interested in, and I think I kind of work it out on the panel or try to express it. That's why I'll even use photos from my mother's side, my father's side, and go way back into the archives, even the present, while I try to show the hybridity of the different sides.

As somebody who grew up in LA, do you naturally develop the idea of LA being a cinematic city, or the place where people come to be movie stars or find their paradise? Are you conscious of that?

I think early on, through graffiti, I was able to investigate the city even more. We were listening to rap music because it was the 1990s and I was a teenager and LA had some big names. That was kind of the soundtrack. So, through the music and having friends in different parts of the city, finding those little nooks of spaces where different and certain groups of people live, you start to understand that it's really a dynamic kind of place. You know that there are layers. You learn that at an early age; it wasn't just Burbank and the backdrops of Warner Brothers or whatever.

So many people come here with their own version of California that they're building, and they only have a certain kind of relationship with the land. But it's one of those things where you can dig deep. That's what I do with the work. It's like I transport myself to when I was a teenager, writing on things in specific areas that don't exist anymore, places and surfaces that I sample, or what I think about when I'm painting or putting together a piece.

There are many layers to Los Angeles, and in a relatively short time period of time! These layers only represent the last 100 years. There is this hyperactivity of change and environment that is different from any other place on earth.

It's definitely one of those places that feels that it's still in process, or kind of like it has not yet arrived, and that's okay. It's one of those things that I think about a lot. I think that it’s definitely okay to be a city that's evolving or just in progress.

That’s just so perfect, but I do have to ask what you think you learned from graffiti. And do those lessons change with age?

Man, that's a good question. I don't get asked that question a lot. It's more just, "You did that? Cool." When I was a teenager and even in my twenties, I didn't appreciate graffiti like I do now. I don't know if that makes sense. Because, as I started to move into the art world, when I started doing it, showing in galleries, I didn't know anyone. I didn't know my cousin's uncle was a gallery owner! I got into graffiti when I was maybe 11 or 12 years old and saw Henry Chalfant’s book, Spraycan Art. My brother probably brought it home from the library, and it was so amazing. I was already sketching and drawing, and they were taking those characters I was sketching and drawing and putting them on the sides of buildings. "Well, how did they do that?" A spray can.

Graffiti taught me discipline and also about just going out there and doing things, versus having permission or getting sanctioned. It taught me how to look at materials differently. Because those guys were taking stuff from the hardware store! I think Mark Bradford said that if you're just buying materials from the art store, you're probably not doing anything interesting. All that shit connected in my head. I was like, wow. Because then I was interested in the materials. And I wanted to add to the conversation versus just kind of like… I'm not trying to be Rembrandt, I'm not trying to be Reubens. You know what I mean? I just want to express the time that we're living in and things that we can speak about, or think about art as artifacts.

It must have given you courage, too, because you have a particularly vast body of work, as in, "I can do neons, I can do paintings. I can do political work, I can embrace and challenge peoples' perceptions of what the art world actually is, what is actually going on around you.” That takes courage.

You know, that's something we don't talk about a lot. But graffiti does give you courage. You don't ask permission, you just do it, and I love that. Because I never wanted to be in this position where I have to ask permission to make something in my studio. That's crazy. At a very young age, I talked about it all the time, although I was very shy and didn't really talk to anyone in my elementary school and my middle school. They thought I didn't speak English and they put me in ESL classes. But my preferred method of communication was the visual.

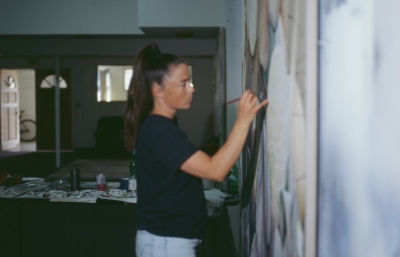

Also, graffiti as an entry point to painting teaches you to paint big. That was a very important time for me because that gave me the confidence to understand that, yeah, I can go large, I can go medium, I can attack a bigger piece. When I was producing some of the earlier pieces that were bigger, they were, like, "Why is it so big? Why are you doing it this way?" It's because I'm comfortable moving this way. I feel that in the new studio I have, I can work like that. It's wide, just kind of broad strokes. Graffiti taught me to organize myself and to put something together. It's all in there, it's all in that toolbox.

You just said you were quiet for a long time. Again, there’s this dichotomy where you're quiet but still making work that speaks loudly and supports large groups of people. Your political voice has become stronger over the years, hasn’t it?

Again, I probably could credit rap and then graffiti. But also there were people I was around at a very young age who were speaking out and being present, trying to speak truth to power.

I was very introverted. When I was a teenager, I wasn't a social kind of person. I guess, in a way, the work speaks for me. I wouldn't want to just be talking about the work that I'm doing. Then it's weird because it talks down. It's like, I don't really want to talk too much about it. I can tell you what I was thinking about it if you have questions, I'm definitely down. But it's like, just go look at the work and make up your own mind. That said, I’ve become more comfortable now, talking about the work.

When I started wanting to show my work at a young age, I just wanted to connect with people. In terms of the images that I make, maybe stop the viewer in their tracks and then just add to the conversation. But also, that's something I never really thought about, or didn't really see from this point of view before, meaning even the materials I use, the places that I collage together; maybe those places have been discounted and people just don't even look at those spaces, places, people and materials. I want to paint a whole new kind of image, so people can say to themselves, “That's familiar." It's really direct, man. That's why I'm saying when you see something good, it's very direct. Sometimes it can be just pen to paper. That’s moving to me.

What's the first piece of art that moved you?

The first experience that I had with art was at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena. I don't know if there was a specific piece, but probably a Matisse. And when you see a good piece of art, you just understand why everyone there is looking at it. I understood, early on, why people wanted to come to the museum, a place that’s there for anyone interested in seeing the work. Now I can articulate that as these are receipts from people living and wanting to make images and color and add to the conversation. Yeah, it was probably Matisse. I think about the past a lot now, what art I loved, how I started, because these days I'm trying to access that kind of innocence, the peacefulness of making work and being by myself, just in the studio working. I'm trying to re-access those times when I was a five or six year old and just making things for my mother.

You know why? Because you have a kid now.

I didn't think about that, but yeah. Just seeing how she wants to see everything up close, how she focuses on it. But you're right, it's like I'm re-accessing all those times when art felt honest. I'm always thinking, "Why did I start doing that type of work?”

I wonder, too, since you've been getting more attention and have had some really great institutional support, if thinking about honesty and “Why do I do this?” has become more urgent for you?

It's definitely a marathon, not a race, right? In that it's self care, in a way. Where it's like, I'm not trying to reevaluate my life. I just want to have those energies near me, the energy of when I first started. I think the balance needs to be there, so I tried to access that. I'm not one of those people that have been chewed up and spit out. It could easily be that way. Because if it's burnout and you're just burnt out, then your work is burnt out. I didn't want and still don’t want that.

Before we go, let’s get back to neon. You referenced Tracey Emin to me earlier, but tell me more about what neon has allowed you to achieve with your artwork?

I wanted it to look like I took it from Whittier Boulevard, one of the stores, that you could hang it in a gallery but then also take that piece from the gallery and put it back in a liquor store. It was straightforward; it wasn't trying to be sexy. The medium is that already. It was just one of those things that I wanted to push back. I wanted the work to push back.

I've been asking this to every single artist pretty much for the last 18 months because I just think it's a valid question: what does urgency mean to you now?

It's weird because when I'm making work, I feel there's an urgency to put it out. With the Pee-Chee folder work, I felt like it was super urgent. I did a lot of work with that. It was a limited palette, so I would just kind of crank them out, and it was almost like honing in on those kinds of chops. But urgency to me right now is to keep producing work that speaks to something I'm feeling, something the United States of America is feeling? Then really making sure that it gets presented in the right light.