You can play the guessing game as much as you want, but it’s difficult to identify artists who could be dropped into a different time period or era and thrive. Marcel Dzama, the Canadian-born, NYC-based fine artist, who exists at the intersection of so much recent art culture in so many styles and mediums, is my ideal time traveler.

All images courtesy David Zwirner New York/London unless noted otherwise

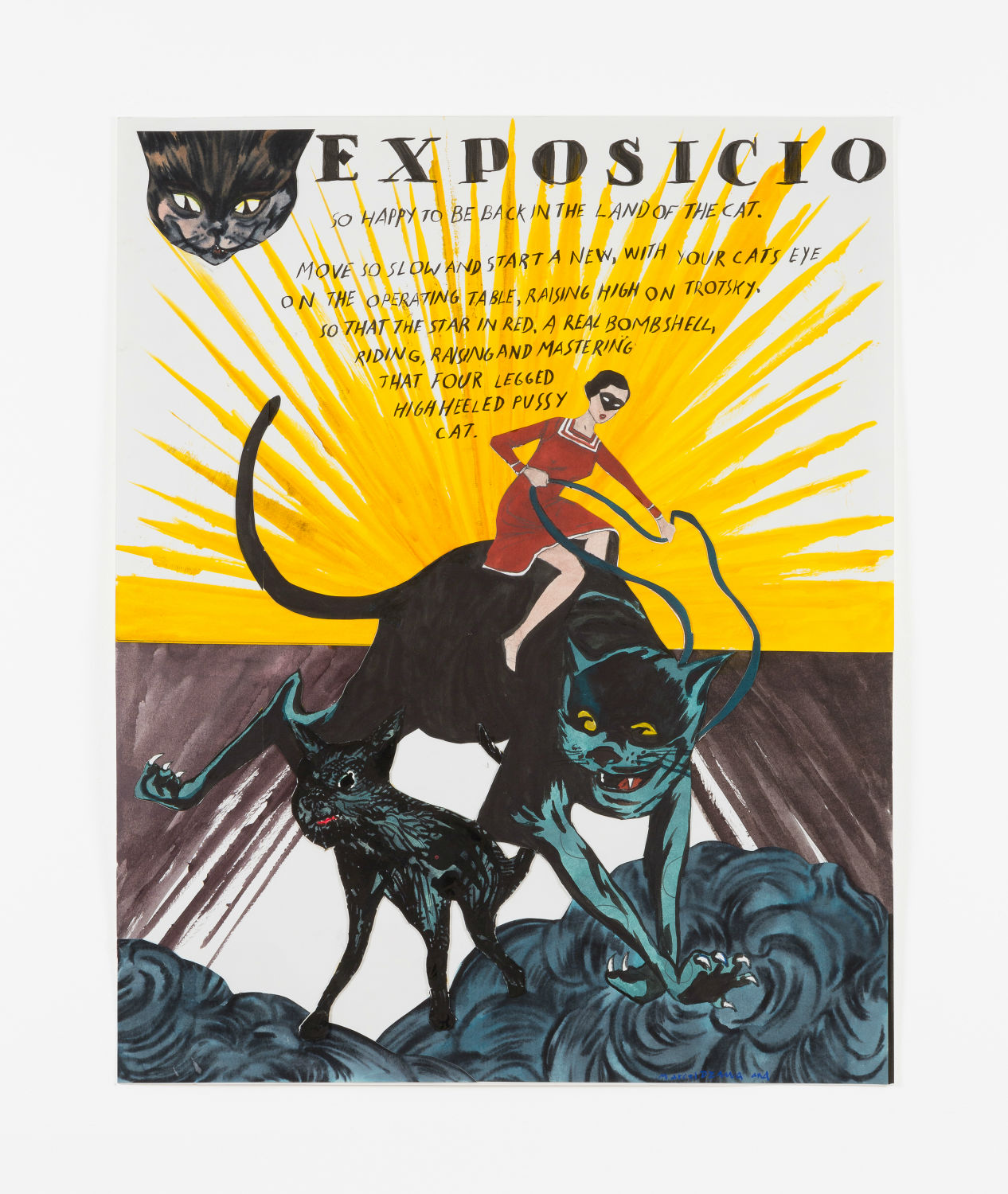

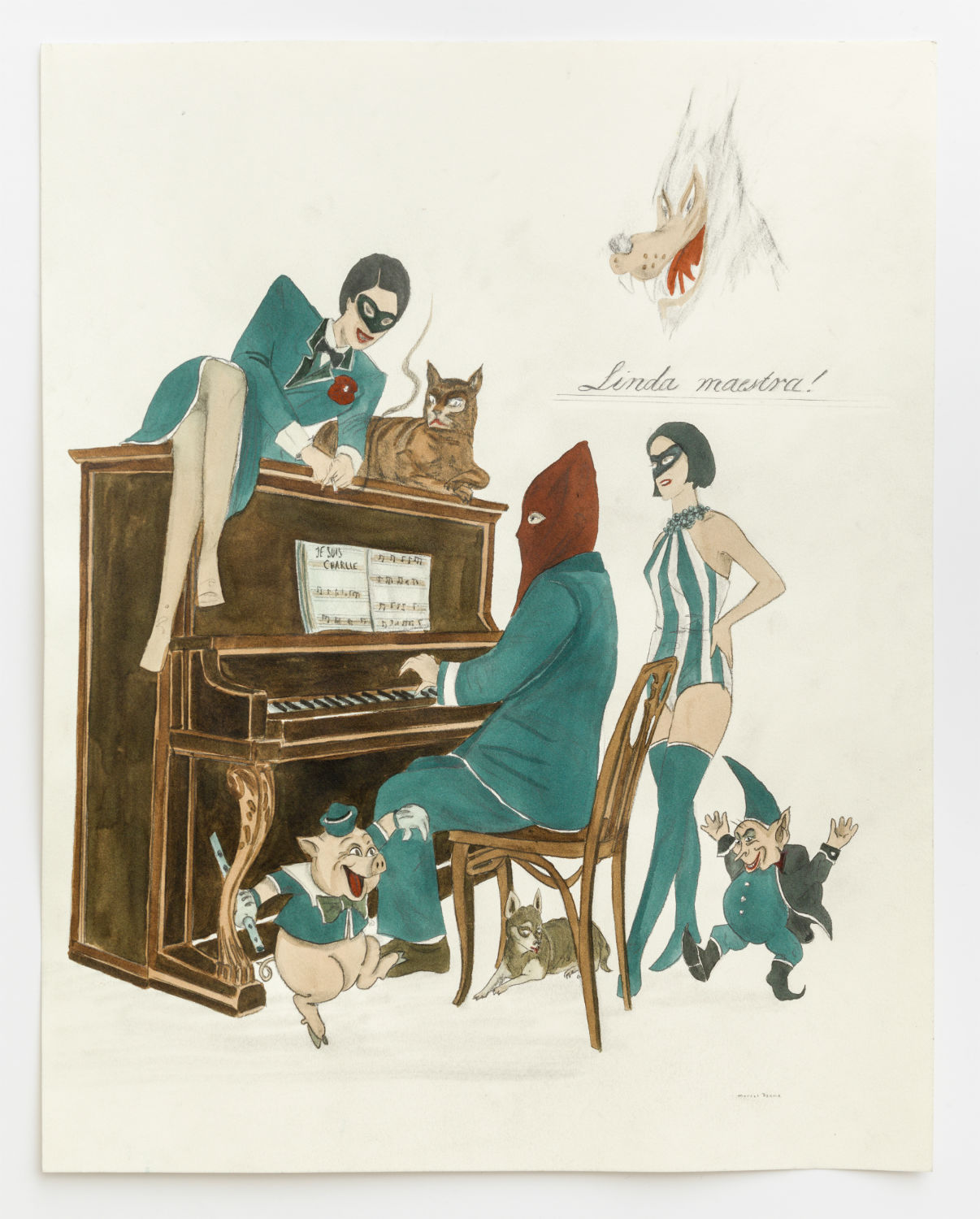

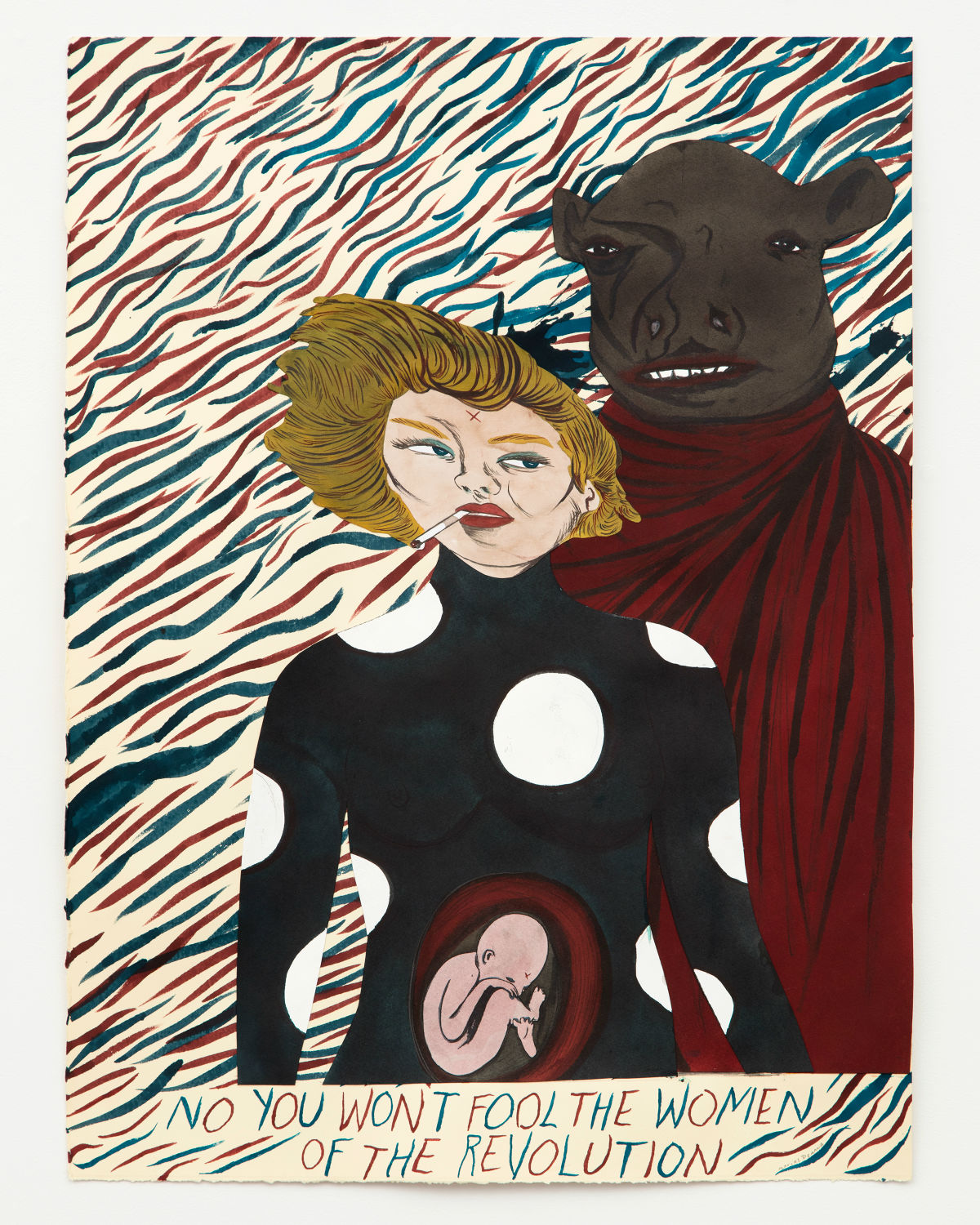

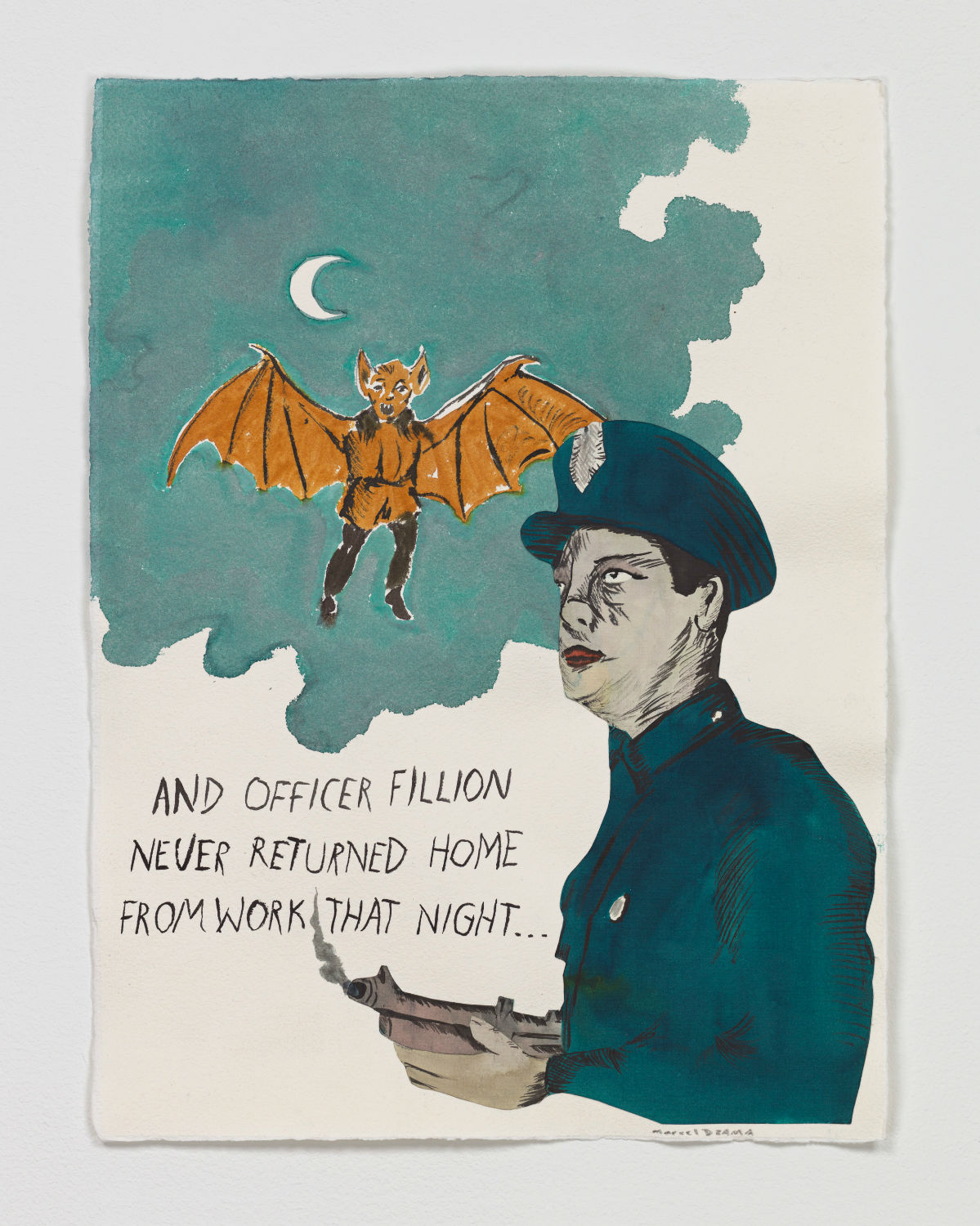

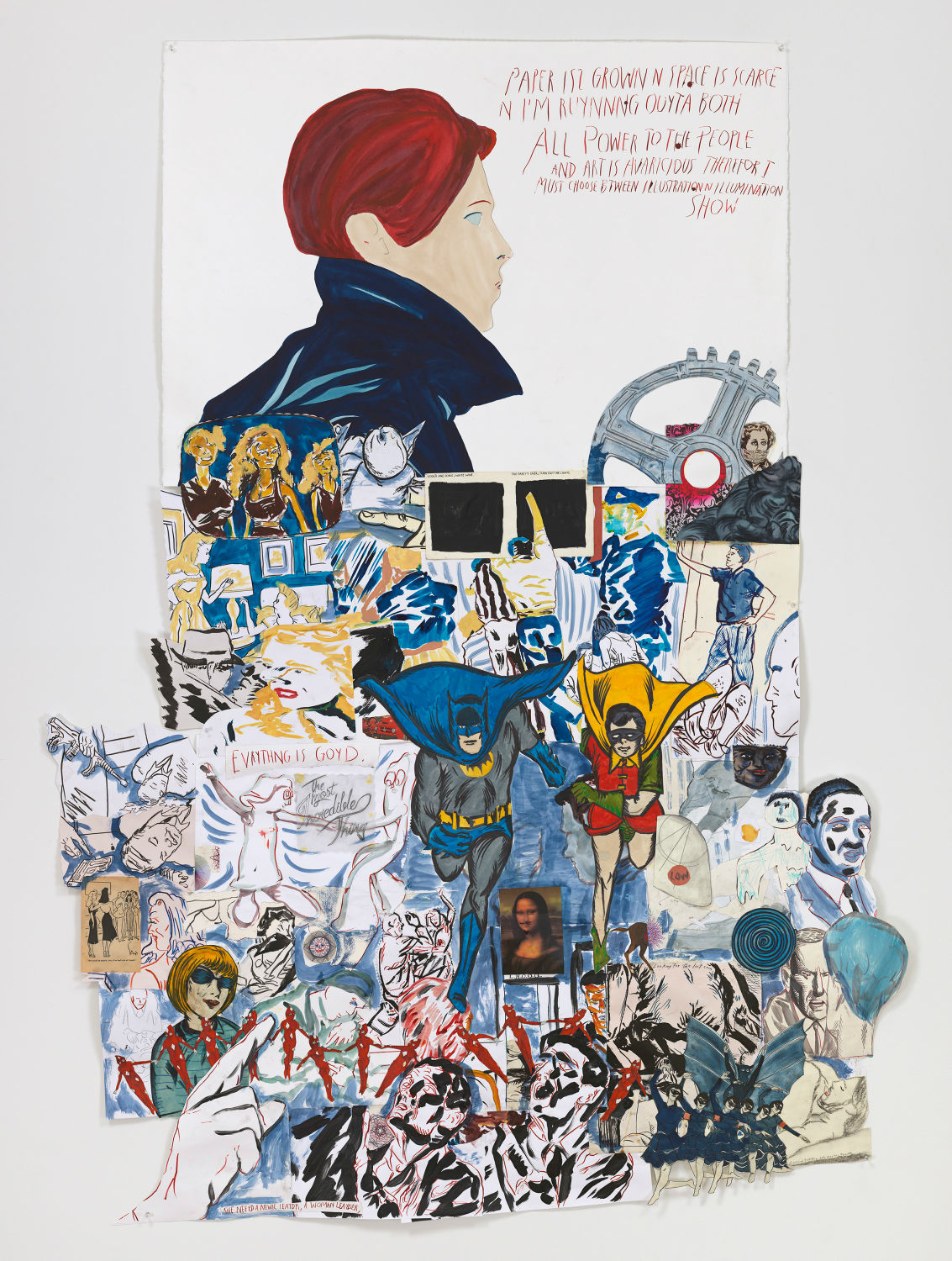

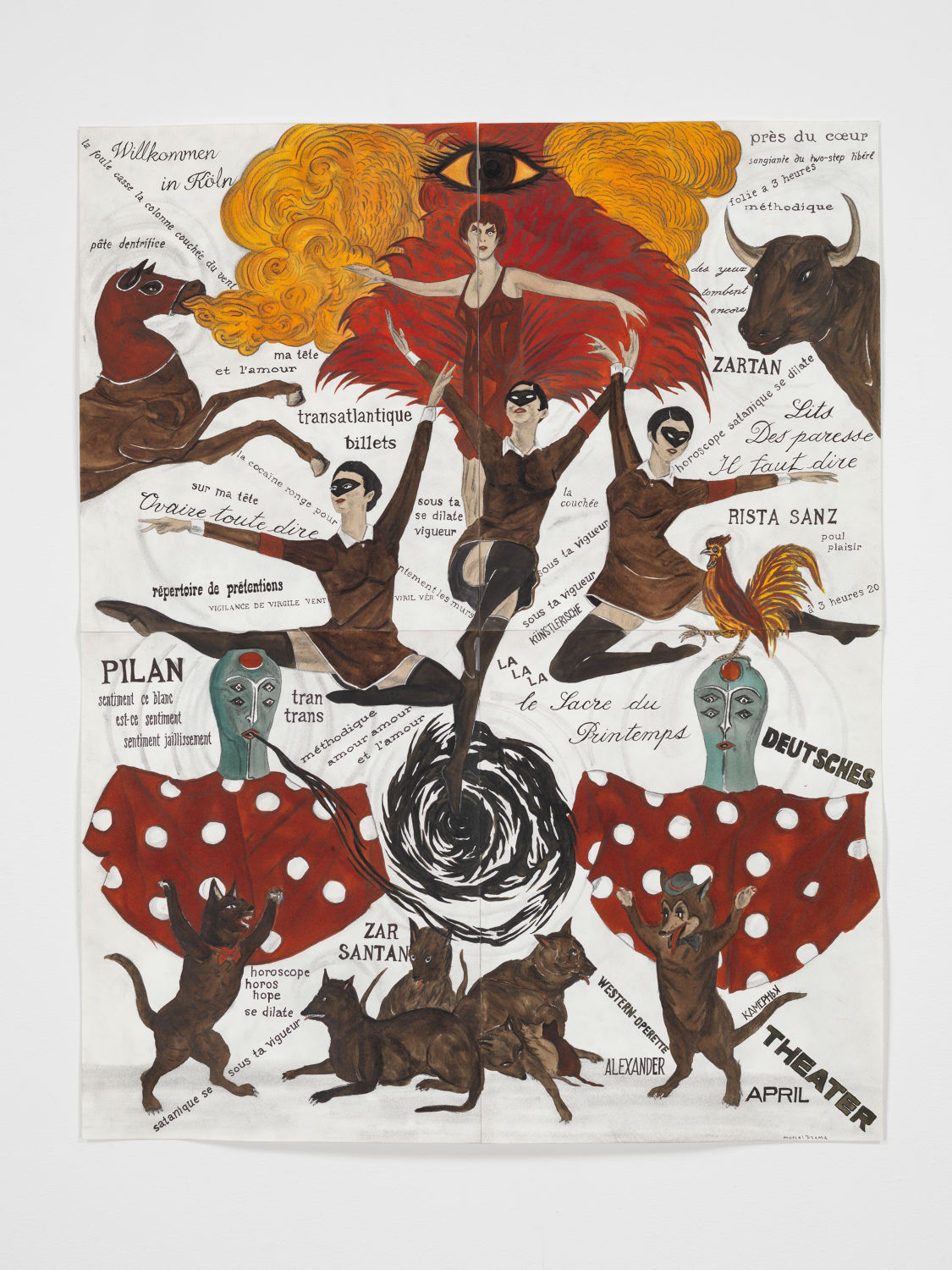

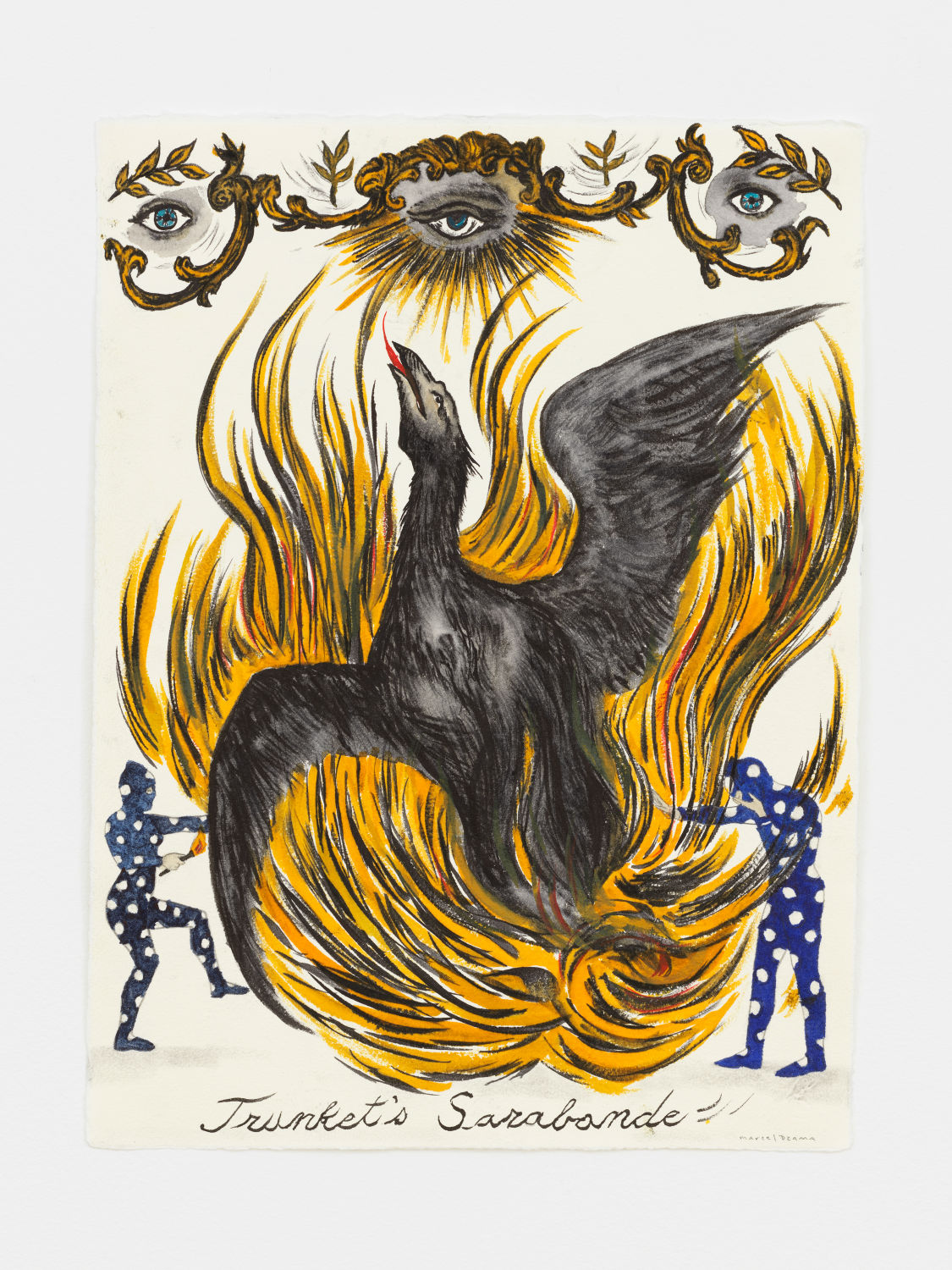

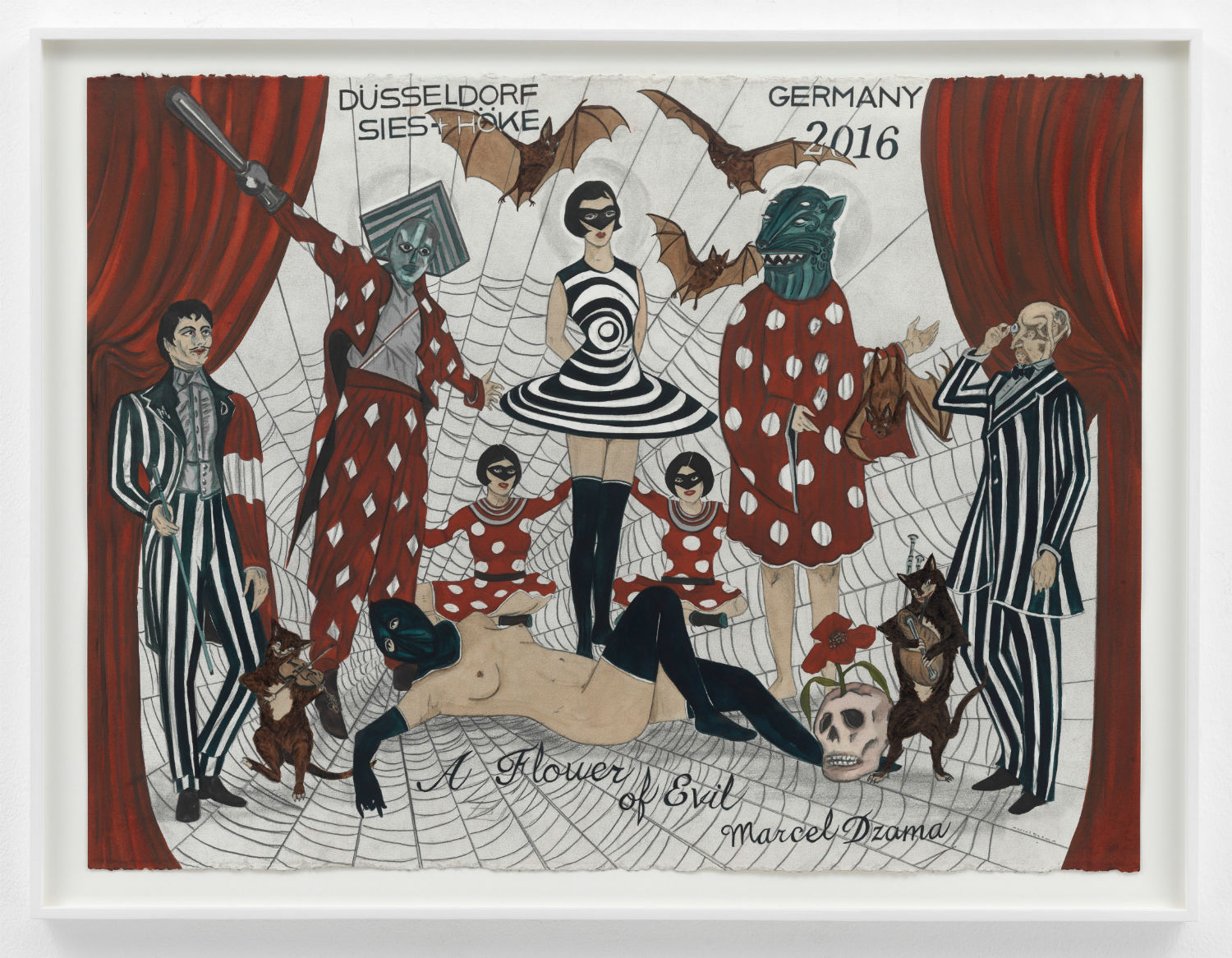

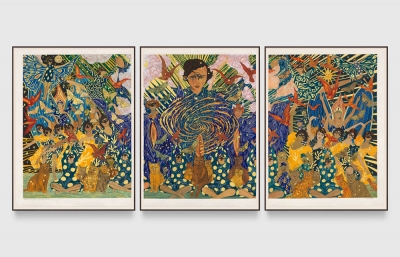

He is a prolific drawer, as well as filmmaker, installation and sculpture artist, musician, costume designer, and one of the most sought-after collaborators within the aforementioned categories. The aesthetic of his work, figurative scenes embedded in the history of surrealism, Dada, Duchamp, 1950s literature and punk rock, streams the consciousness of who we are and where we are going. He is the old soul with modernity at his fingertips.

The list of artists Dzama has worked with includes the most influential and creative minds: Dave Eggers, Kim Gordon, Arcade Fire, Beck, Spike Jonze, and even recent art direction for the NYC Ballet. He is also a founding member of the crucial Royal Art Lodge, a drawing group born in 1996 at the University of Manitoba, which, although it disbanded almost 10 years ago, is still talked about in folkloric reverence. Perhaps even more significantly, he has achieved international success with museum retrospectives, as well as exhibitions at the contemporary art powerhouse, David Zwirner Gallery. Needless to say, Dzama is a universe creator, and the art world circles in his orbit.

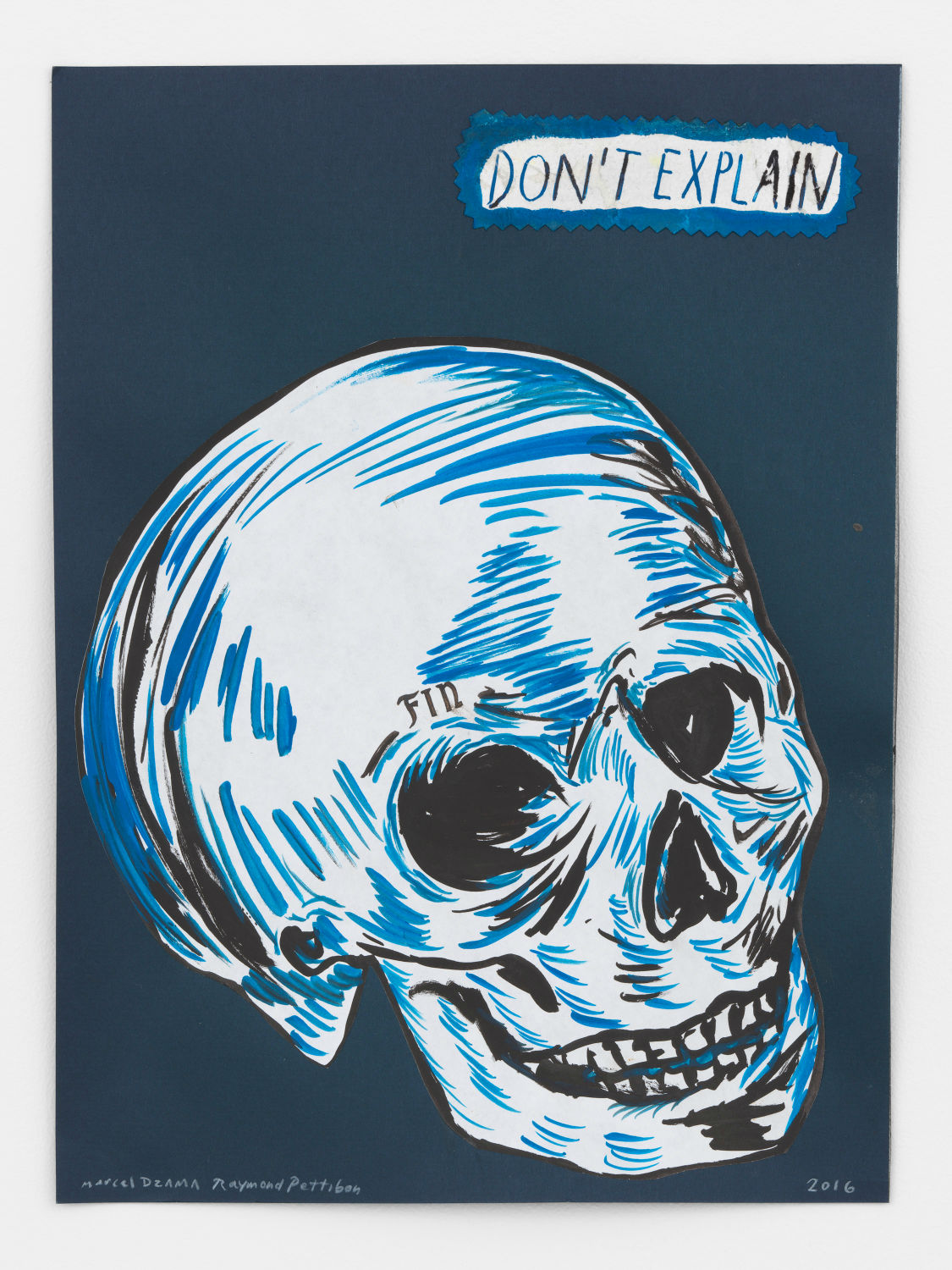

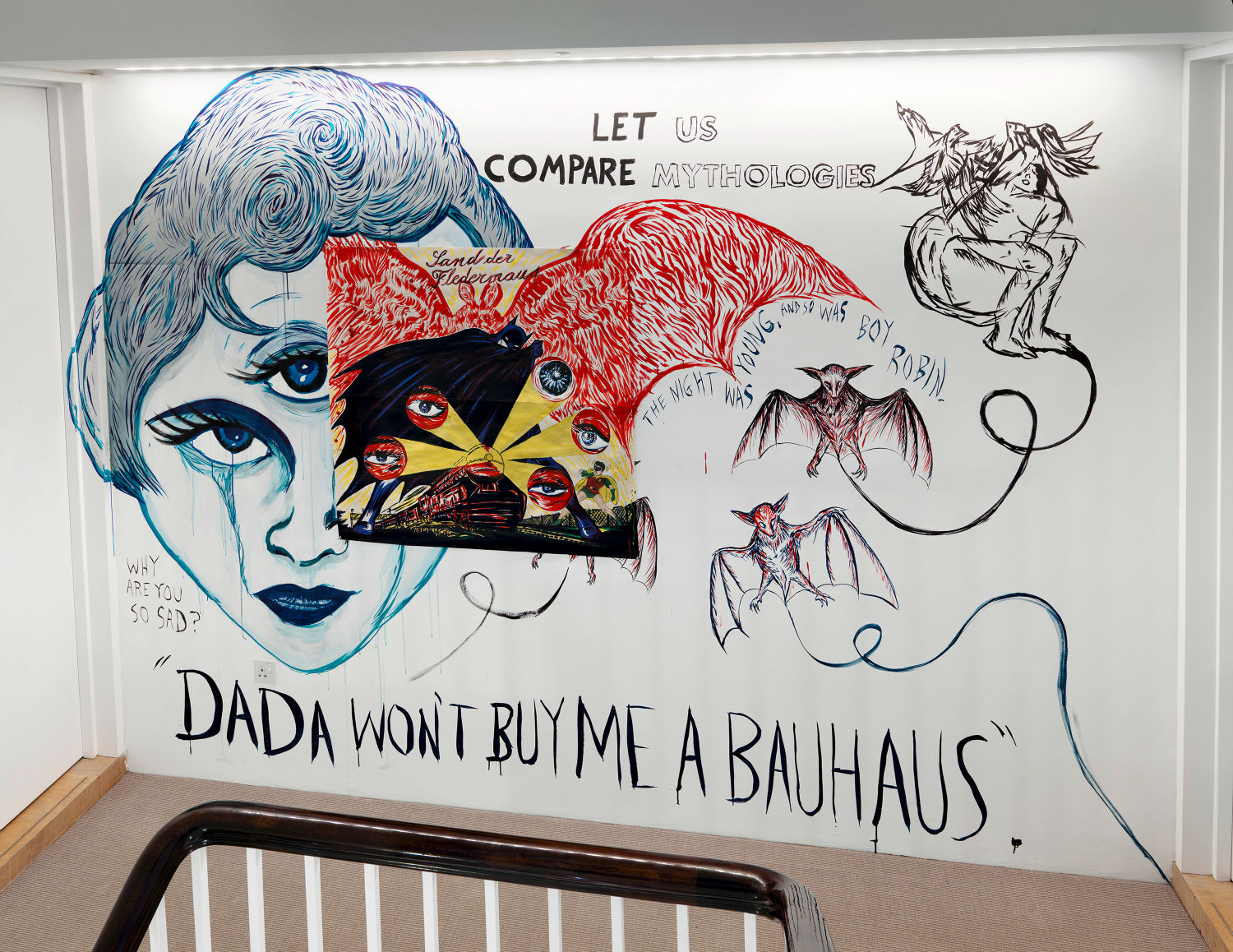

In late 2015, Dzama teamed up with another hero of the underground, Raymond Pettibon, on what would become two collaborative solo shows and zines shown at Zwirner’s spaces in NYC and London. The pairing not only speaks to the unique history of alternative art cultures born out of music and comics, but also to the immediacy and political impact that drawing captures in a world dominated by new media. Dzama and I sat down at his Brooklyn studio just after the US election, and a few weeks after I visited his and Raymond Pettibon’s show in London, where their improvisational style seemed to respond to the world’s events in almost journalistic fashion.

Read this feature and more in the February 2017 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine.

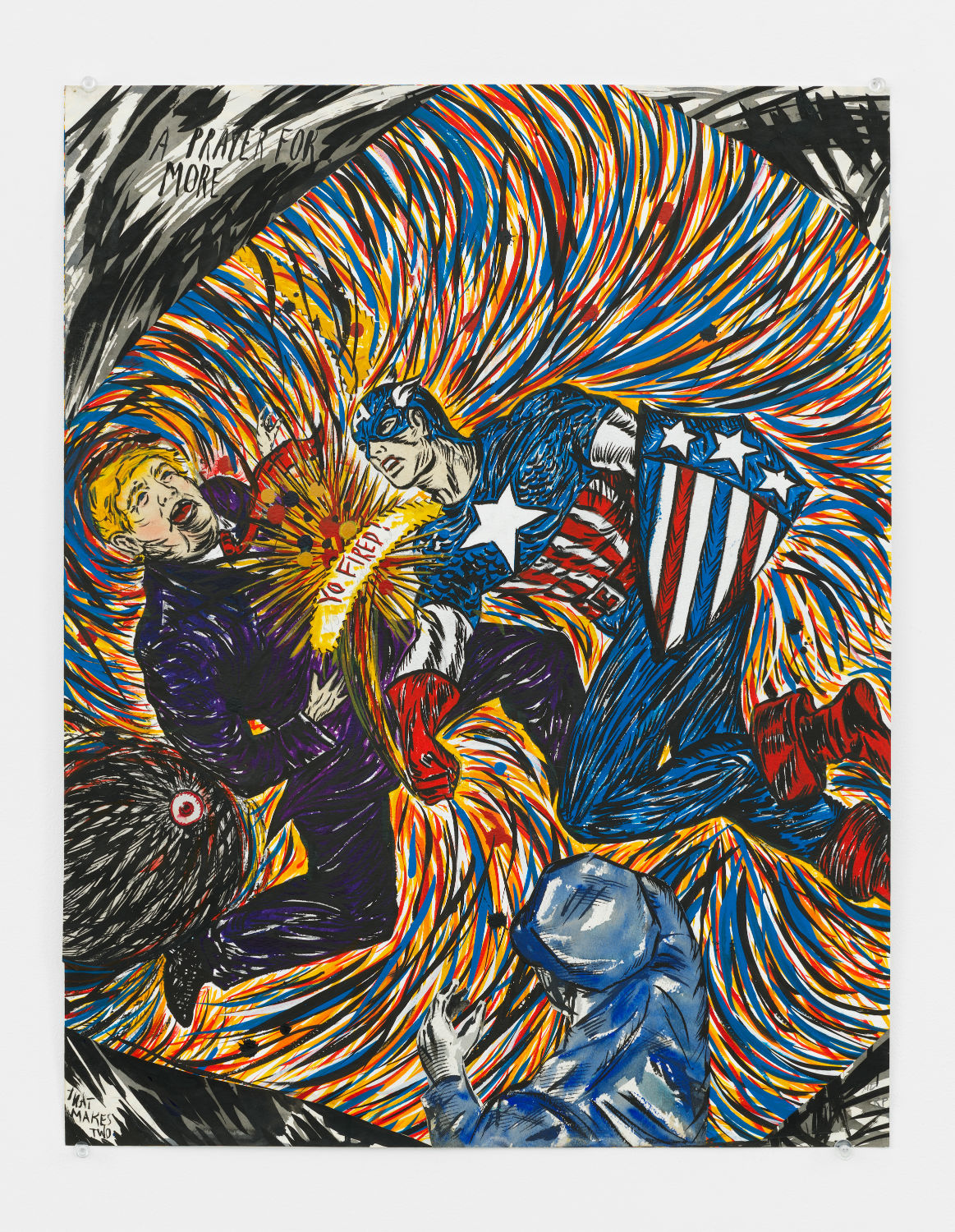

Evan Pricco: You and Raymond Pettibon have been working with these superhero motifs in your works together, and I know you were thinking about doing some Trump work even before the election. I think we have to start with this superhero/supervillain idea, because it feels like we have a supervillain now.

Marcel Dzama: A few days before the election, Raymond did a portrait of Trump. I think it said, "You're hired." Raymond was predicting it better than I was. And then, just after the election this week, we collaborated on the one where Captain America is punching Trump and saying, “Yo Fired!”

Maybe this is a sensitive question, but is there something fascinating about artists’ reactions to times like this?

I think it's an important time for artists to make as much noise about it as we can. I don't know how to phrase that properly, but I also felt that the trajectory of things was moving forward and it was good. Then, all of a sudden, you hit these nose dives. One foot forward and ten back.

Let us compare mythologies installation with Raymond Pettibon at David Zwirner, London

The way that you present your drawings, and even the performance stuff you do, seems era-less. But you interject politics into the work all the time, perhaps just not literally. You are influenced by Dada, which came out of WWI, right in the heart of an era that saw, perhaps, the greatest world changes in terms of how we settle conflict. It seems like there's an interesting lineage in your work that feels heightened in these times.

During the Bush years, I was very obsessed with all of that, because disgust at the war really motivated me to do work. This reaction to what was going on.

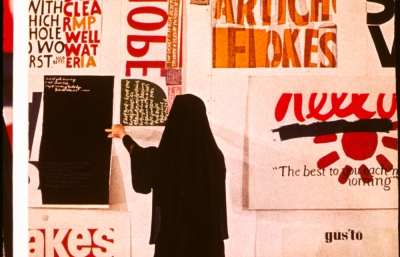

Drawing is so perfectly immediate for times like these. Other mediums can't actually cover ground as easily or urgently. You can make a film with overarching themes, but drawing is directly here, right now. When you draw, you can be a lot more literal.

There is that instant gratification from doing a drawing. It's so immediate. That was one good thing about the collaborative shows with Raymond. We were able to comment on what was happening the day before the show opened; it was fresh off that table we worked on.

It's almost like you're a newspaper journalist, in a way, this old-school way of political discourse.

There’s something nice about actually being timely about it, being of the moment, at least. In the last few solo shows, I've usually made a film, and then I'd have the drawings I made that storyboard the film. After the film was done, I'd also do drawings that were almost sequels or prequels to the film. The drawings all made sense together.

Then, for Raymond and I, at the recent show at David Zwirner in London, there was Trump’s election on the horizon, Brexit, more cop shootings of unarmed black men, and Standing Rock was happening. Standing Rock was actually the centerpiece of the show, this anti-oil stance. We had a giant oil explosion and the environment running amok. It was a very apocalyptic show, which makes sense for now, even. More so, unfortunately.

Do you consider drawing to be the core of what you do?

Yeah. I do move into film a lot. I always have. Even in art school, I would do short videos and things like that, but I got known for drawing first.

You grew up in Winnipeg, which has some significant art institutions and infrastructure, despite being a small/big city. Would you credit this underrated hub as an influence in your creative growth?

The city has an amazing Inuit art history and collection. That was really influential in my early drawings. There's also this history of the city that peaked in the 1920s, when a lot of buildings were in their heyday. You can see the decay, but they're still there. There's old ads written on buildings for some dish soap or something from that era. There's this nice nostalgia, this idea that there was a better time. In 1919, there was this huge strike and they tried to reproduce the Bolshevik Revolution in Winnipeg. There was this whole movement there.

And that ties together how your work has both elements of theatrics and the aesthetics of a revolution.

That may not have happened consciously, but probably subconsciously. My father was also a war history buff, so I watched a lot of World War II documentaries at a very young age. It was kind of drilled in pretty early.

Portrait by Bryan Derballa

When did your style, as we start to see it now, begin to emerge?

It happened out of a tragedy. I was living with my parents when I was in art school, and we had a big house fire where all my art was destroyed. After, we were put in this hotel near the airport, called the Airliner Inn. When I was there, I did all these drawings on the hotel stationery because it was my thesis year of university. My presentation before that was all these big paintings because I had all this room in my parent’s basement to work. Suddenly, I was in a hotel, with basically a small space to walk around. I drew on my bed the whole time, did these small drawings that kind of became what you see, at least at the beginning of my art career. All a blank background with one or two characters doing some kind of surrealist thing. It was very depressing, but it was also very freeing having nothing to hold you back. No possessions.

It was all drawings. I was also very poor, too, and didn’t really have art supplies. The paintings I did before were all house paint works. It wasn't like it was so tragic that they were lost. They weren't these masterful oil paintings or anything. It was 1996, the same year that we started the Royal Art Lodge. My uncle, Neil Farber, my sister, and a few friends from university, we started getting together every Wednesday at the beginning. Then it became every Sunday. We had meetings at my hotel and stuff.

That started at the hotel?! We can jump ahead, then, because with Royal Art Lodge, and working with musicians and people like Dave Eggers and Spike Jonze, and now Raymond, you evidently thrive with collaboration, which not everybody does.

I think it might be a Canadian thing.

Why was collaboration so necessary for you?

We were all in each other's bands, too. It kind of felt nice to have a group of friends, to have a reason to get together. We're all socially awkward, too. Almost none of us even drink or anything, so it was like, "Let's get together and we'll draw." Anytime we tried to have a party, it was a huge failure. We'd just end up drawing and not talking.

If you look back right now on those hotel drawings, do you like them?

Yeah. They came from much more of that Inuit influence that is so prevalent in Winnipeg. It's almost like a mix of children's illustrations with Inuit art. It feels like a different person. It's me, and I still like some, but maybe not all of it. I was very prolific, but very minimal. There were only two characters on the page. I would do... I don't know, 30 drawings a day, but there wasn't that much to them.

I remember, it must've been 2006, and Richard Heller, the gallery where you were showing then, was one of the few galleries with this really strong fine art drawing program. I thought it was a really good time for that style.

It was when drawing came into the art world. I think that actually had a lot to do with Raymond Pettibon. He opened that door, and if he hadn't have done that, I don't think I would be in the art world at all. I really owe a lot to Raymond for that as well.

Neither of you is afraid to do a lot of work. It's not that you don’t edit, but the volume of output is compelling. That's why I love drawing. In this day and age, where there is so much information, it matches the times.

That helps inform the other parts of my art, too, like the dioramas. Those came about after I spent time in Guadalajara, Mexico. The people that brought me there were asking me to do something, and I kept seeing all these little sculptures of saints in the marketplace in town. All these nativity scenes. You could go buy these little clay characters. They weren't just Jesus and Mary. There were little devils and stuff and they were holding bags of money or being mischievous. I thought, "I'd like to recreate something like that." I started working in ceramics there, making these dioramas. Kind of recreating nativity scenes, I guess. And all of them were based on my drawings.

Is that how you always work?

Yes, even with film. I usually storyboard everything with drawings. In the silent film that I did with Kim Gordon, Une Danse Des Bouffons (The Jester’s Dance), we were filming in this small space. Then, all of a sudden, we had a day to use this really large space, so the cameraman and I wrote a whole new theme for her to run around in this maze of stairways and things. Then we had this weird gate, so I'd light up these weird soldier creatures in there. It added a lot more dimension to the scene. I’m always open, especially for locations. Locations can actually change scripts for me.

I know you had this chess thing for a bit, right?

I was obsessed with it for a long time, right around the time I got obsessed with Marcel Duchamp. I was living near Washington Square Park, and there were two chess stores where you can go to play people. Also, in the park, you could play. There you play for money. And I only did it once, to say I did it. I was always very shy, but I would go and watch. I was finding my attention span was very... well, I wanted to start thinking further ahead, and I thought it would be good to slow down and learn how to think ahead of the game.

Is that what you like about Duchamp?

Yes, the almost pre-planning of everything. I find that since having a kid, I haven't played chess at all. With pre-planning, you don't have much time anymore. I just go on instinct now.

For my shows, I would have the walls covered with drawings, and I did this over and over again. Then at some point, I thought, "I want to add sculpture or videos." I wanted to base the show around a theme. So now I have all these different directions I can go, and it's nice to have that.

How does that idea work with the shows you are doing with Raymond? Why does it work with him?

I think we have a lot in common. We probably have similar working class backgrounds. And we both were, I think, just obsessed with, like you said, this output of work at an early age. He also came from the punk scene. I can't say that I came from that scene, but I came around the time of the resurgence of Punk the 1990s. The whole grunge thing.

And I love his artwork. I've been a fan of his since I knew what conceptual or contemporary art was. He was probably the first contemporary artist I knew because of the Sonic Youth Goo album cover he did in 1990.

We're working backwards here. What was your first thing, the thing that got you into drawing?

I was always drawing. As a little kid, even. I was making these weird poetry journal things. I don't know what it was, these scrapbooks with drawings and writing. I was always writing bad poetry, and I always thought of it. Later, that way of thinking was used for songs. It came out of that. It was totally surreal, definitely heavy on the William Burroughs influence. A lot of chopping up and collaging... I had that going. That was because of seeing Naked Lunch.

Did you think you were going to be a writer?

No. I have dyslexia and I'm terrible at writing anything. It's very affordable, and as a kid, you just have a pen and paper around, and you do that. I remember my dad would bring this paper back from the bake shop that had grease on one side, but the other side was clean. It was this really nice cardboard lined paper, and I used to draw on that all the time. It used to ruin some of the drawings if I piled them on top of each other.

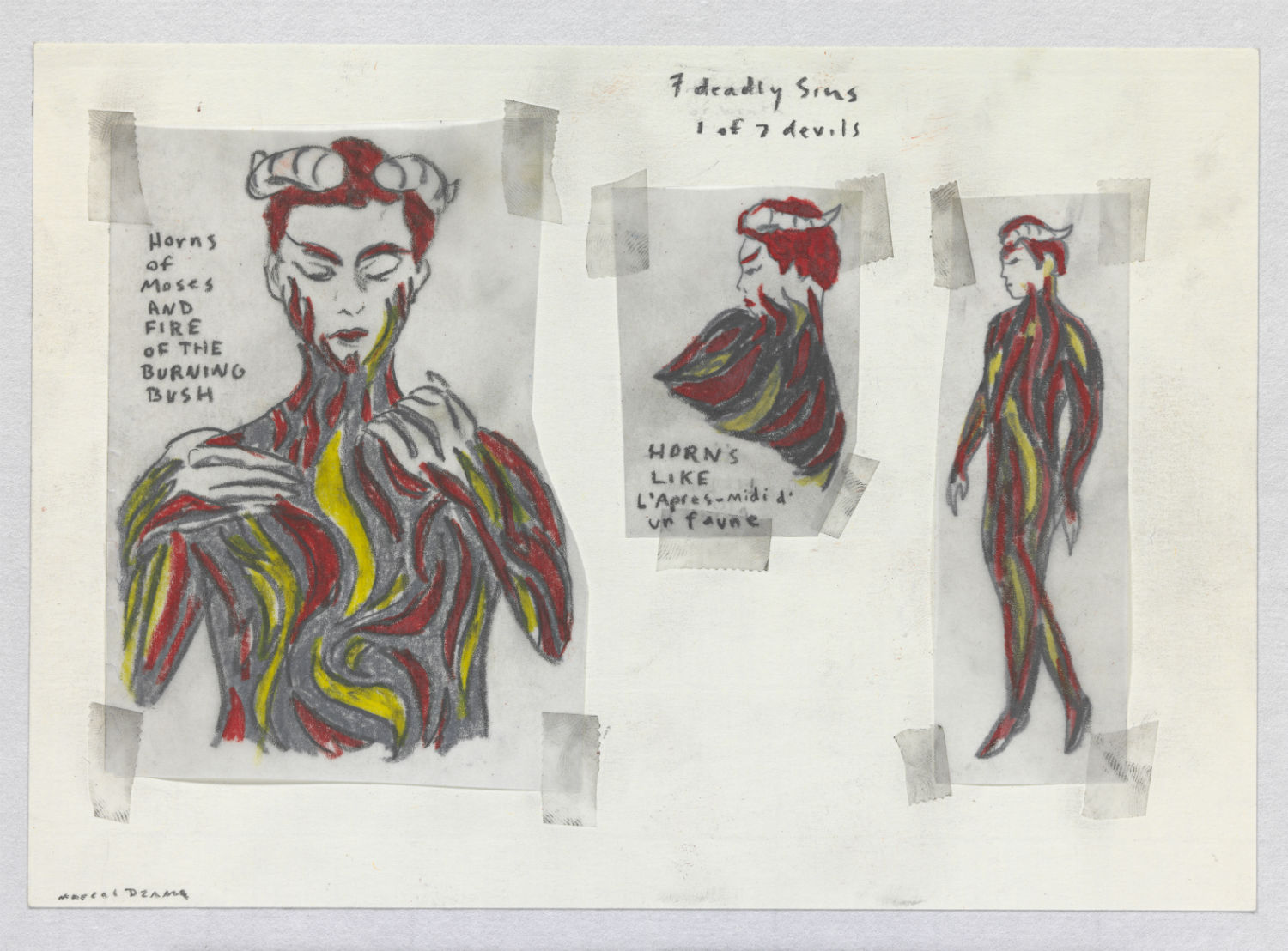

In the 1980s, my parents bought me this Fisher Price camera that recorded on cassette tapes. I didn't know how lucky I was until later. I would just plug it straight into a VHS player and press record. Then I'd just make films in my room. I would always make the costumes and had my sister, uncle or dad be the actors. And they weren’t actors, so would always smile if I was filming, so I'd have to put a mask on them. That's how my style of film was.

Did you design the masks and costumes?

At the very beginning, yes. I didn't know how to do paper mache or anything yet. Then, once I got more ambitious in the films, I started making paper mache costumes.

So, even early on, you were into this. Everything I've seen of your film stuff, what I love about it is that it's hi-fi/lo-fi. It feels like everything's done by hand, as opposed to doing super special effects or elaborate dress, yet it’s high concept.

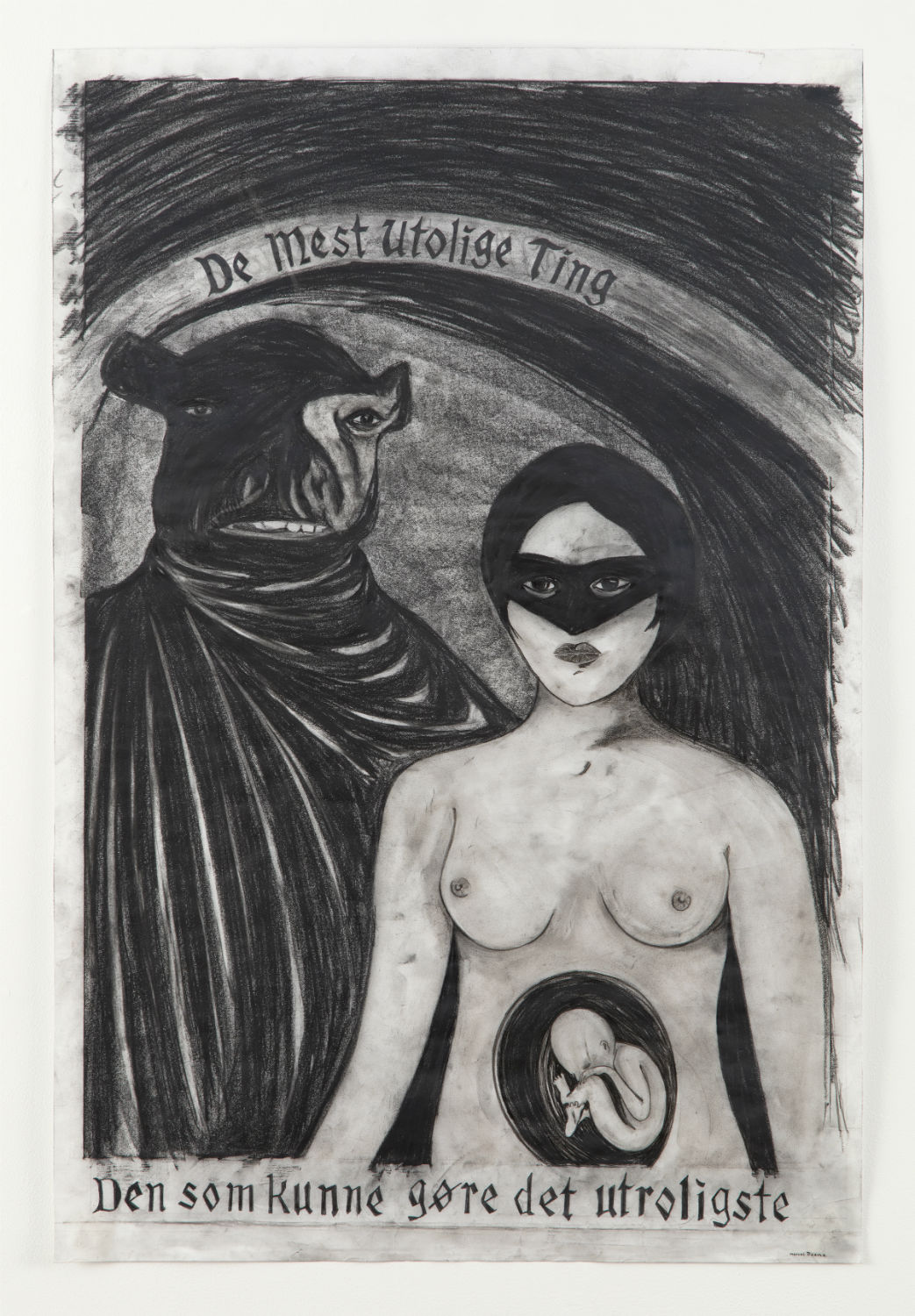

My favorite thing in films are in-camera tricks. Those early French ones, like Méliès’s A Trip to the Moon, in like, 1902. Even when I art-directed the NYC Ballet, The Most Incredible Thing, earlier this year, I wanted the costumes to look like they came from the past, but as if they were also predicting the future. I usually like that aesthetic. It’s handmade, trying to see the future, but it's not like, “The Future.”

We have come full circle. Your characters are timeless but looking to a future.

Trying to predict the future, telling the story of what is to come. . .

----

Originally published in the February 2017 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine, on newsstands worldwide and in our web store.