Charles Moffett is pleased to present The Provocateurs, the first New York solo exhibition for Kenosha, Wisconsin-based artist Keith Jackson. This marks the self-taught painter’s inaugural exhibition with Charles Moffett following his official representation with the gallery in spring 2023.

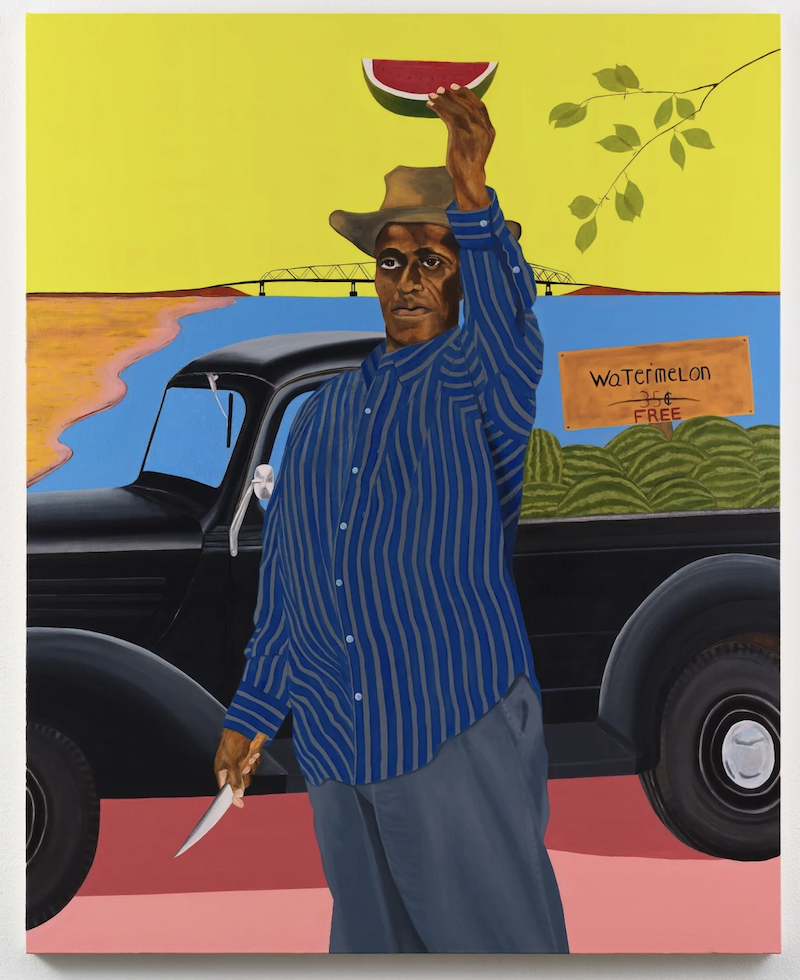

Working in brightly-hued oil paint applied either on canvas or linen, Jackson paints to capture and communicate the simultaneously profound yet every-day memories of his childhood growing up in rural Missouri. One of nine siblings, he has a deeply-held passion for his family roots. As the second-youngest child, many of his paintings capture his siblings and extended family at moments that he wouldn’t be able to naturally recall, drawing upon treasured black-and-white family photographs and the stories that he and his siblings tell one another as the inspirations for his works. Jackson’s final paintings never directly reproduce a photograph; rather, the artist pulls elements from different photographs and combines them with representations of meaningful objects from his past as well as iconic visual emblems of the era.

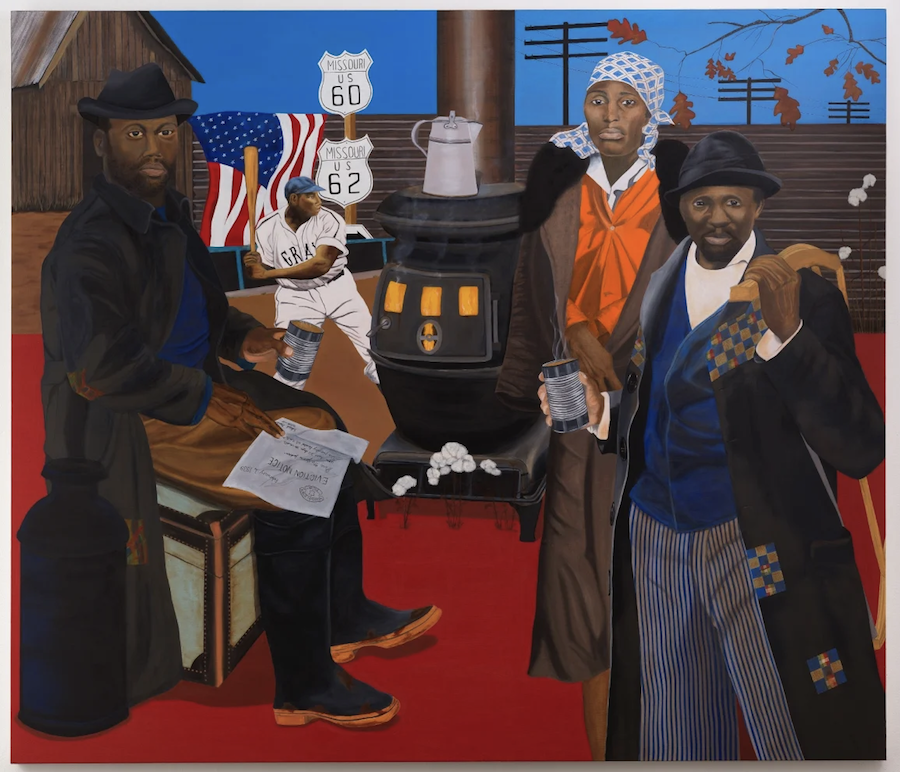

For The Provocateurs, Jackson has continued to mine his extended family’s life-experiences; but, this time he ventures into a new terrain of examining the ways in which his family has been shaped by the broader social and political histories of the rural South in the 1930s. The genesis of this exhibition came when the artist’s children gifted him the book Freedom: A Photographic History of the African American Struggle. As he read through it, Jackson was surprised to see a chapter dedicated to an event that radically shook the place he called home yet one he had never heard of — the 1939 Sharecropper Roadside Demonstration in Southeast Missouri: a brave and powerful collective action taken by more than 1,500 men, women, and children alongside US Highways 60 and 61 in the lowlands of southeast Missouri to protest against the racist and impoverishing implementation of New Deal agricultural policy. Jackson has been captivated by this event — the historical details of its motivations, aims, and impacts, the heroic figures and everyday people that mounted it, and perhaps most critically, why it is that, despite taking place in the very same lowlands that have been home to him and generations of his family before him, no one in his life had ever learned about or recalled this major event in our national history.

While his research has not determined if his ancestors specifically participated in the demonstration, he has confirmed that they were directly impacted by the event that catalyzed the protest —the federal government’s decision in 1937 to break the Mississippi River levee that had been protecting the rich cotton land in the Missouri Bootheel, ultimately giving the 12,000 tenants and sharecroppers of that land, including Jackson’s family, three days’ notice to abandon their homes and take what possessions they could before the entire area was buried in icy floodwater. Killing 400 people, displacing thousands, devastating one million acres in farmland, and causing an estimated $500 million in damage, that event is considered a major inflection point in motivating the sharecroppers of the Missouri Bootheel to organize and ultimately to stage the strike and winter roadside demonstration in 1939. For Jackson, upon learning the details of the 1937 levee break, he immediately connected it to what his mother used to say…“we lost the farm in the flood”.

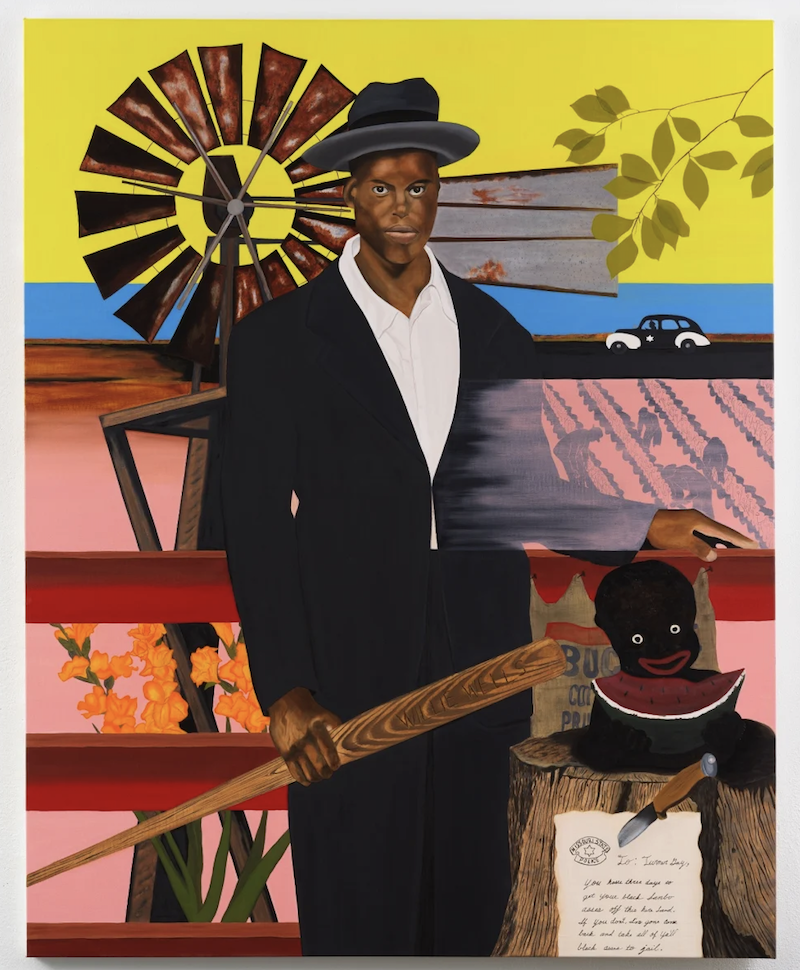

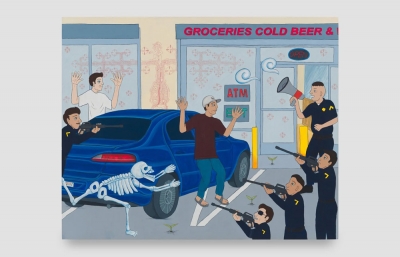

This collision — between Jackson’s family stories, legacies, and remembrances and this rarely-mentioned chapter in the long history of African American political protest — forms the foundation of the artist’s new body of paintings. Take for example the painting Defiant. The central figure is based upon Jackson’s maternal uncle, a preacher and a man of deep faith. Jackson based the portrayal of his uncle on a family photo, likely taken around the same time as the Sharecropper Roadside Demonstration, and grounds him within a rural scene that combines various histories, memories, and symbols. In the background, a police car ominously travels along the road, sharecroppers are hunched over in the fields of cotton, and a rusting windmill stands tall. While in the foreground, the figure tightly grips a baseball bat — a stance of defiance against the persistent racism and impoverishing social and economic policies that threaten him, emblematized by the racist Sambo figure perched on the tree stump and the eviction notice knifed into the wood giving him days’ notice to leave his home. Other symbols and visual cues abound throughout the show — the gladiolus flowers represent resilience, strength and faith; coat patches shown in the painting Got Hustled are inspired by patterns from Jackson’s mother’s quilts the family has preserved; and cotton plants appear as a constant reminder of the abundance and value of this land and the labor extorted to extract it.

Approaching his practice with a rare combination of joy, gratitude, and reverence that comes with age, Jackson creates paintings that are at once immensely personal and poignant and also provocative, challenging, and eye-opening. Through The Provocateurs, Jackson pulls out and sheds a proud light on a period of our national history that seems to otherwise be lost to the shadows — urging us to share and tell our collective histories, and never fall victim to the misconceptions that our past has no bearing on our present.