A show that just came down that we wanted to make sure we got your attention with was Sarah D’Ambrosio: Brooklyn, Berlin that was on view at MARCH in NYC this past month.

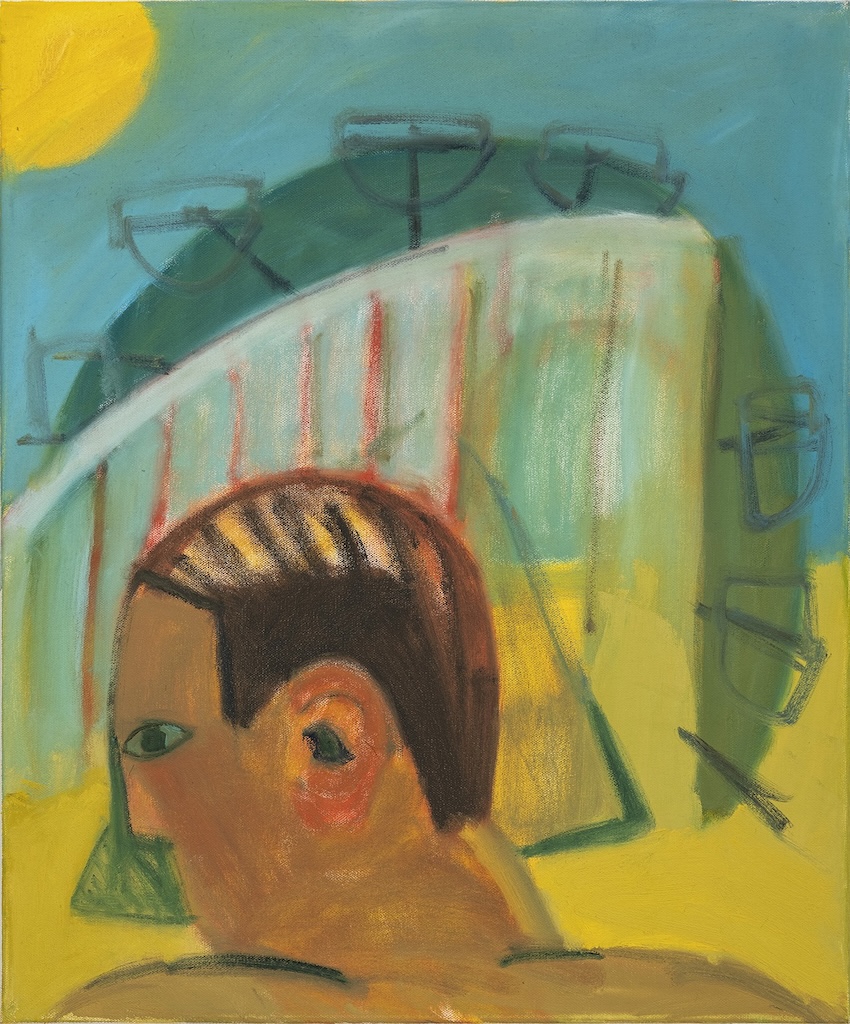

During her childhood in Brooklyn, D’Ambrosio came to understand Coney Island as a place defined by a unique social agreement. The nudity that would shock elsewhere was and is pervasive; bathers of all shapes, sizes, and ages frequent the beach regardless of weather. In The Wave Game and The Liar, carefree bodies leap against Atlantic waves, lost in play. D’Ambrosio considers the familiar area’s contradictions, its “colorful, playful atmosphere and its not-so-picturesque beach mixed with poverty, strangeness, uncleanliness, and tragedy.” Noah’s Wonderwheel and To pitch a tent present the backdrops of these memories, unmistakable architectures where carnival games seduce with worthless prizes and the ocean provides only brief respite from the blazing sun. Yet there exists a shared understanding that despite the public, often-crowded nature of the area, beachgoers are entitled to privacy.

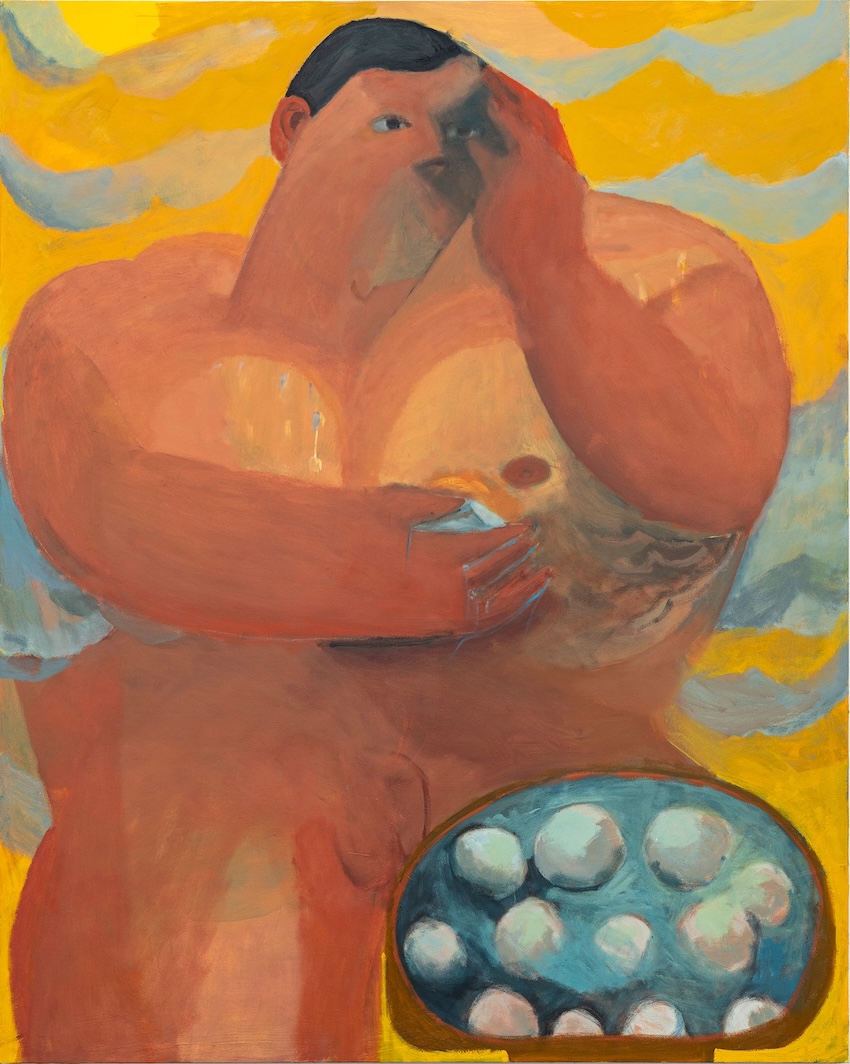

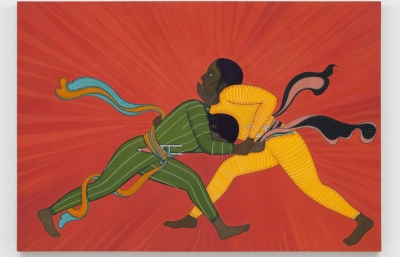

Similarly, during months spent frequenting Krumme Lanke and Berlin’s bathhouses, D’Ambrosio encountered a parallel kind of freedom, enabled by collective respect for rules and directness. She recounts, “In Berlin, you can’t cross on a red light without being scolded by a stranger, but you can swim naked in a public lake, drink in the streets, or spend 24 hours in a nightclub. Those freedoms provide a sense of safety, humanness, and belonging to a bigger community.” Works like Krumme Lanke and Cove Coverage are born from this strictly constructed liberty. Triangulated foliage recalls that of Paul Cézanne, while heavy figures are reminiscent of Marsden Hartley. Their eroticism conjures Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Bathers at Moritzburg (1909–1926), and their jeweled blue palette his Three Bathers (1913).

The paintings of Brooklyn, Berlin are almost entirely rendered in arc-like gestures. The curve of muscles, the swing of an arm, waves, trees, hair, sun, and snowballs offered in the dry sauna echo with a familiar crescent stroke. The draped white cloth of Titian’s The Entombment of Christ (c. 1520) provides the design for this building block, one of few garments present in these unconstrained scenes. Despite their abstractions, each painting reflects a fixed cyclical process; contact leads to departure, beginning seeks end. Drawing from history, memory, limerence, and fantasy, the depicted spaces convey ideal conditions for a sensory liberation. Relation is unrecognizably transformed by a collective thirst for autonomy.