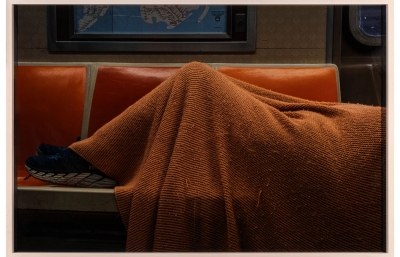

The terrifying immensity of the firmament’s abyss is an illusion, an external reflection of our own abysses, perceived “in a mirror.” We should invert our eyes and practice a sublime astronomy in the infinitude of our heart… If we see the Milky Way, it is because it actually exists in our souls. —Jorge Luis Borges

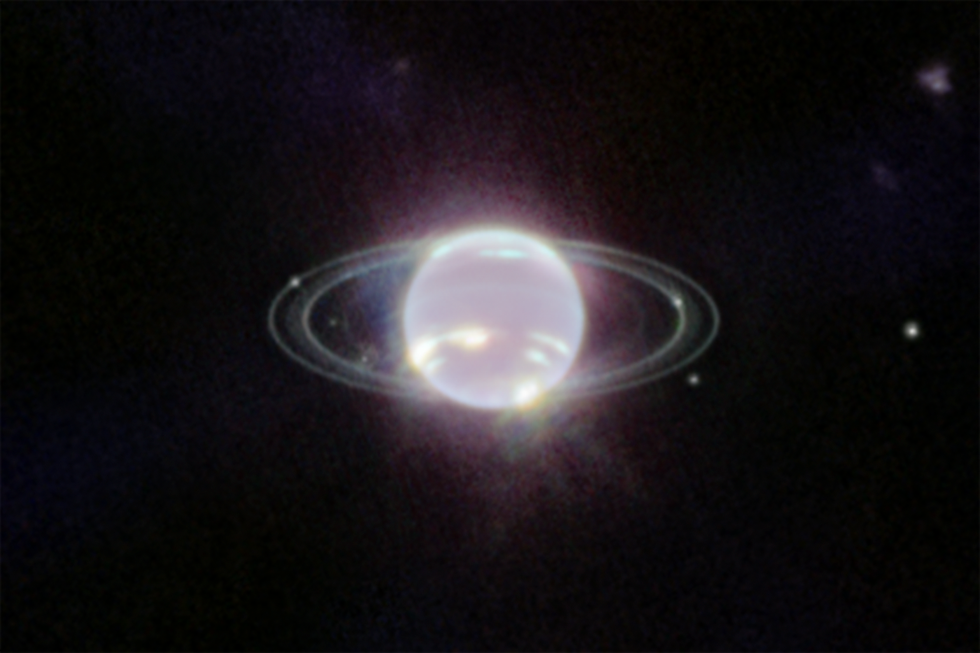

Floating a million miles away, eighteen honeycomb mirrors on the James Webb Space Telescope (Webb) collect the light of the universe and transmit home an image of raw darkness. While it’s not light we have evolved to perceive, we’re becoming quite adept at seeing in the dark, at discovering extraordinary things hidden from these naked eyes.

The universe is mostly empty. It’s how all that light can travel unimpeded over billions of years to reach us. We've always looked up to orient ourselves; the stars have helped us find our way. Yet, it might be the disorientation we feel looking up that is most important. It’s those kinds of feelings, and the primordial questions they so often provoke, that are fundamental motivators in everything created and everything discovered. The curiosity that drives an astrophysicist is not so different from what inspires the artist; both minds are inclined toward awe.

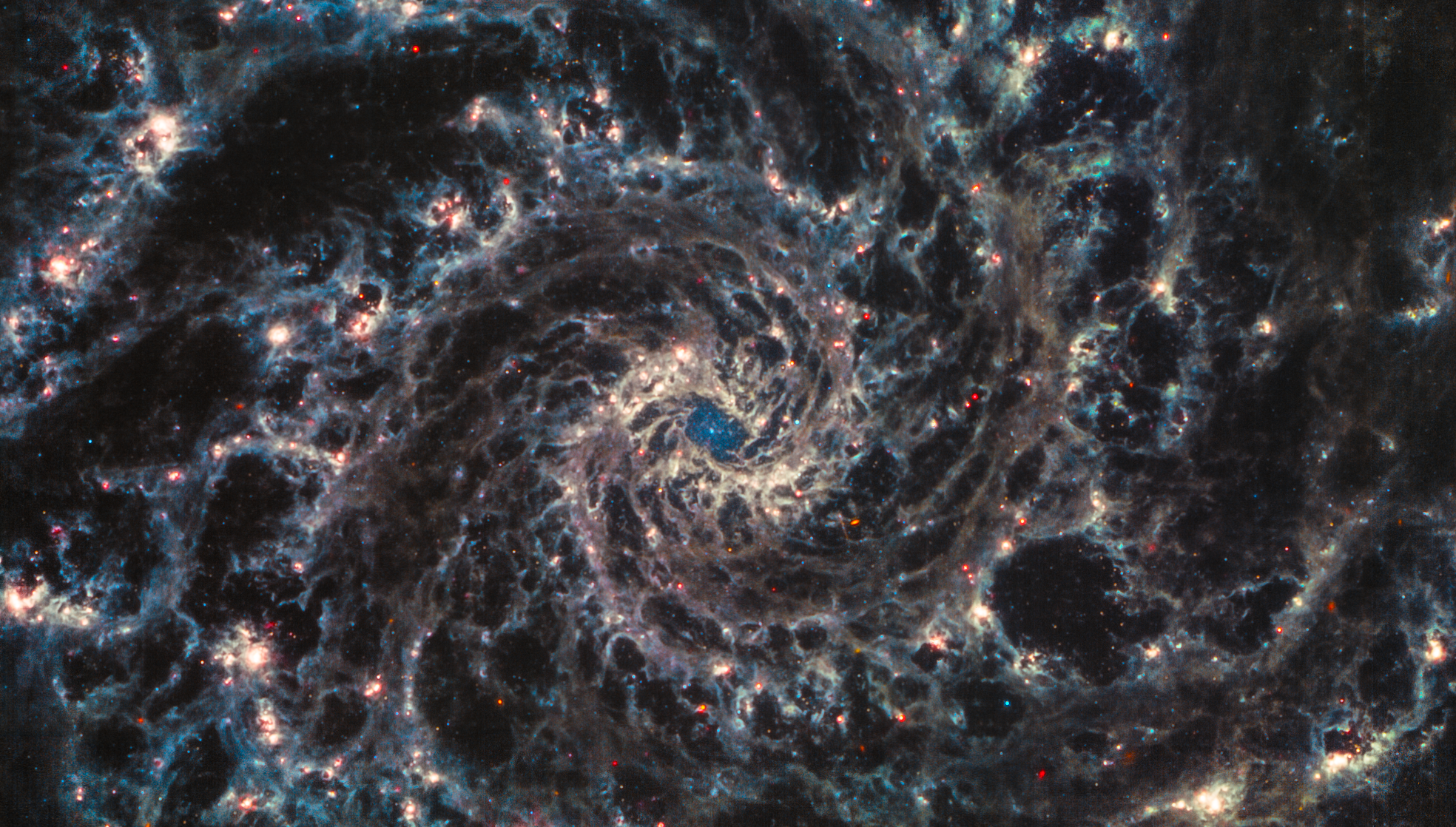

Frank Summers, an astrophysicist at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScl), suggests that the greatest experience for a scientist is "to realize that you don't know what you're talking about." Within those moments, "there’s opportunity for knowledge, opportunity to explore something new." Summers' colleagues at STScl, Joseph DePasquale and Alyssa Pagan, are the first to take the massive amounts of raw data captured by the telescope and composite different filters to reveal the breathtaking photographs of deep space shared with the public. "You can’t see all the information contained in the file," explains DePasquale. "It requires what we call 'stretching,' finding where the details actually exist. And they are usually buried in the darkness."

NASA/Chris Gunn

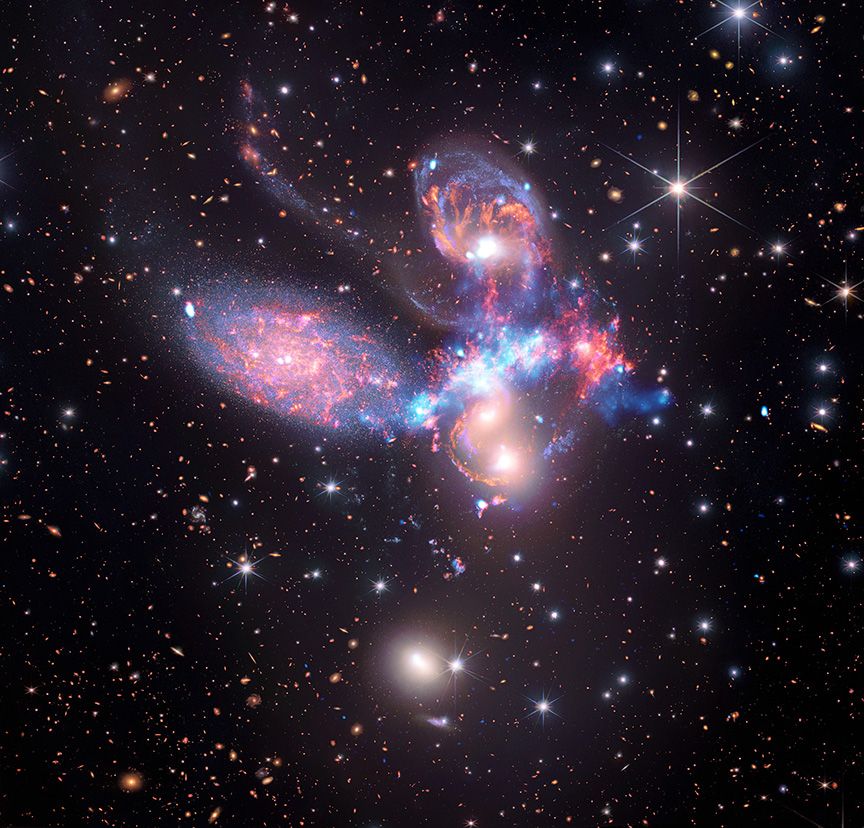

The images, with their infinite seas of swirling galaxies, glistening clouds of celestial dust and haunting towers of interstellar gas, those printed on these pages, are not suitable for scientific analysis. Too much information is obscured to translate the infrared light captured by Webb into the rainbow of colors the human eye can perceive. Gaps exist between objective data and the subjective, visual experience of the universe—but not, perhaps, between beauty and understanding. Where information is obscured, other things are revealed. Pictures are universal. "Once you get past how beautiful it is," reflects Michael Lentz, Lead for NASA Creatives, "then you start to consider what you’re actually looking at… the scale of it, the distance, both physically and temporally, and how amazing that is too, that you're literally looking back in time."

Every photograph is a photograph of the past. Looking at the world, we capture the light of the present, viewing passing moments forever in the future. But looking up, looking out at the stars is our means of time travel. We can capture the light of the past and view it in the present. Both moments are finite, but the connections we can draw to ourselves from either are infinite. "When I look up at the night sky," says Summers, "it’s actually the band of the Milky Way that I orient myself with. I feel at home. I feel like I’m part of our galaxy, and I can really understand our place in it." From our shockingly perfect home, drifting in the glow of a distant star, we are reflecting the light of the universe. —Alex Nicholson

This article was originally published in the Summer 2023 Quarterly