In the summer of 2009, I embarked on a film project with Steve “ESPO” Powers entitled A Love Letter For You. The film was part of a larger project, a love letter to the city of Philadelphia in which Steve and crew reclaimed the rooftops along the Market/Frankford elevated train line. They painted messages of love for the viewing pleasure of all who ride in and out of the city.

One of the main characters in the film was based on a prolific young graffiti writer and talented artist named Agua (a.k.a. Timothy Curtis), who was always running wild and literally “never not having fun.” He would have been in the film himself if he hadn’t been serving out a seven-year jail sentence for failure to accept prosecution. At long last, he’s out and now has the opportunity to self-actualize his artistic career. Fortunately, this gives me the chance to catch up and learn about all things Agua.

Read this feature and more in the April 2017 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine.

Joey Garfield: How did you get the name Agua?

Timothy Curtis: Everyone in West Philly has a tag. Seems like they were born with one. I got one when I was nine and that was PIPE. I started to write because everyone was writing. But the cops became aware of me, so I switched my name. I had been thinking of cool letters to write. When the Puerto Ricans saw a cop they would shout out “Agua Agua Agua!” Like a million times. My friends said it all the time. I specifically remember walking in the parking lot this one day and I was like, yeah... Agua.

Tell me about the characters and faces you’ve developed, which are made up of very specific handstyle gestures similar to tags. Do you see that too? Is that where these faces come from?

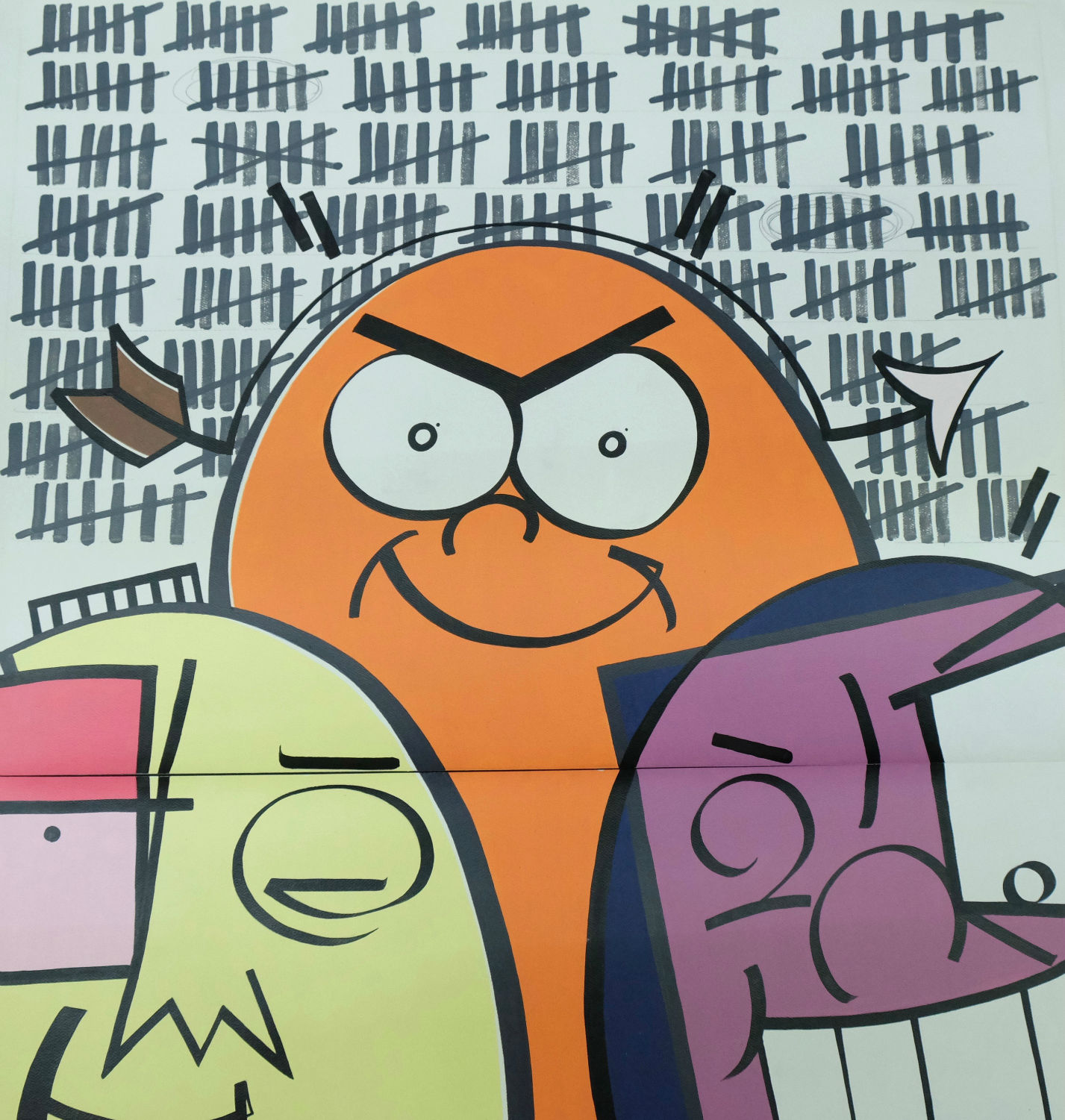

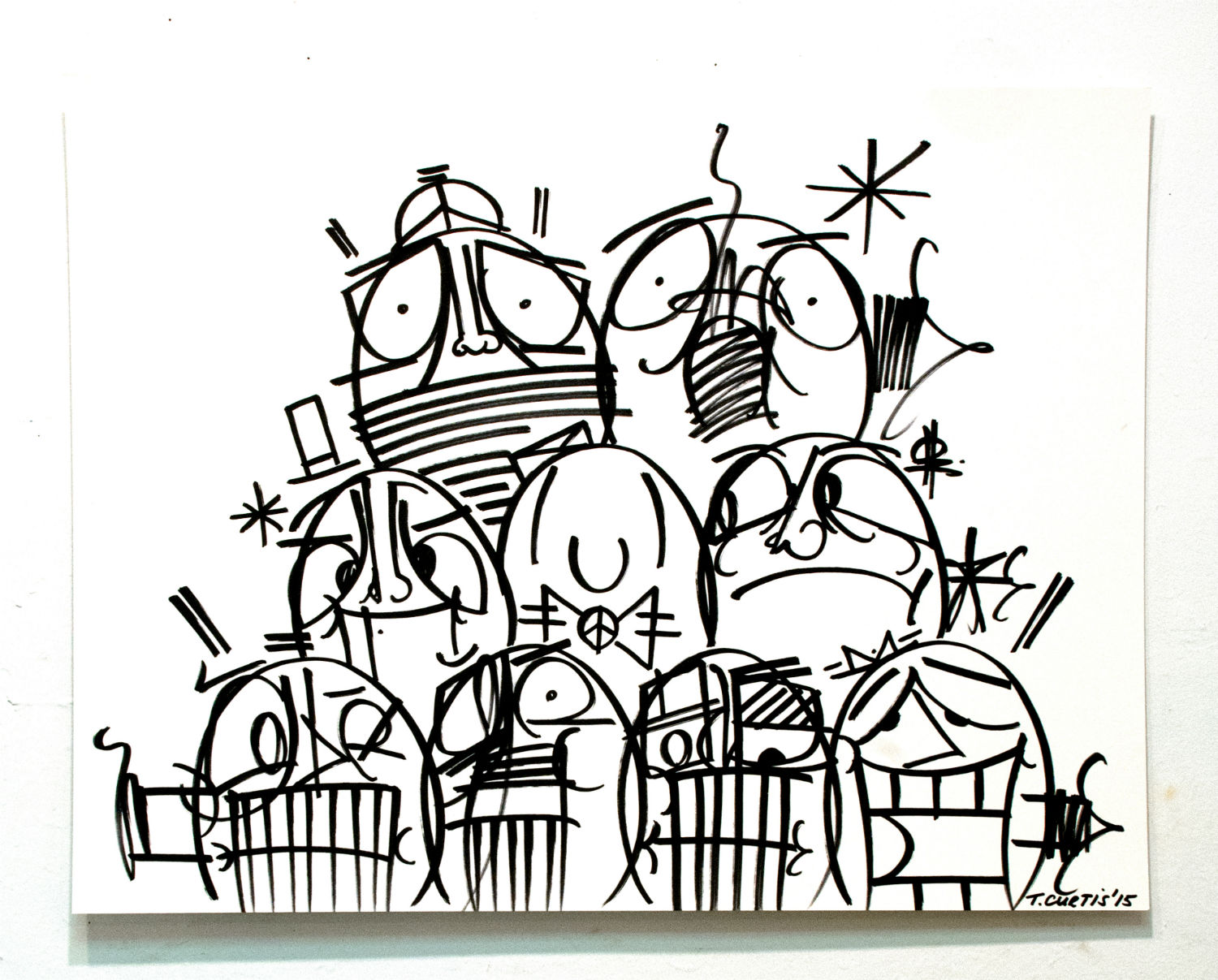

For sure, everything comes from tagging. In Philly, specifically, there is a long history of doing tall tags with faces next to them. In the 1970s, a Philadelphia graffiti writer would put a smiley face next to his name and add a dollar sign, a bow tie, or a top hat. That tradition was carried on for decades by dozens of other Philly writers with their own style and taste. But there were only a few that would really do more than just the traditional Harvey Ball Smiley Face.

I wanted to carry on the tradition as well as create a new history for the city and take it past the plain smiley face. So I started drawing all kinds of faces and stockpiling them. I now have fifteen sketchbooks filled with faces, four to a page, back to back to back. As time went on, they became more and more stylized. When I was on vacation (incarceration), I compiled all my loose pages and had a crackhead count them and put them in books. He stopped at 8,000, but I’ve made so many faces since.

Why have him count, why not you?

I’m not gonna sit there and count. I gave him a pack of Newports. That’s the jailhouse currency: Newports and coffee, so a pack is a good amount. He got his money’s worth. These are just the faces to accompany a tag. They aren’t portraits, line faces or any of the other kinds I got.

What does it take to pull off work that sets you apart? How do you stay distinct?

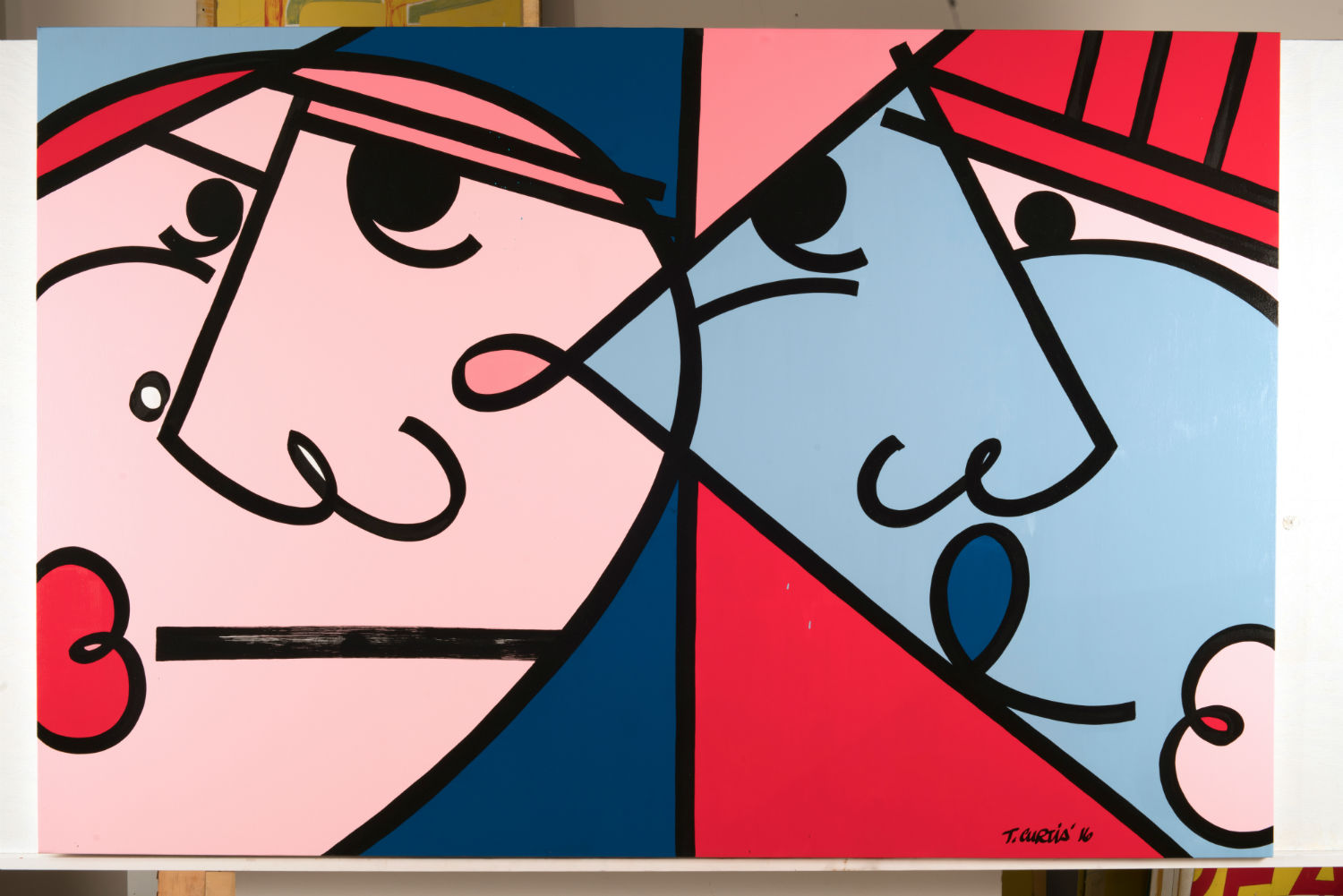

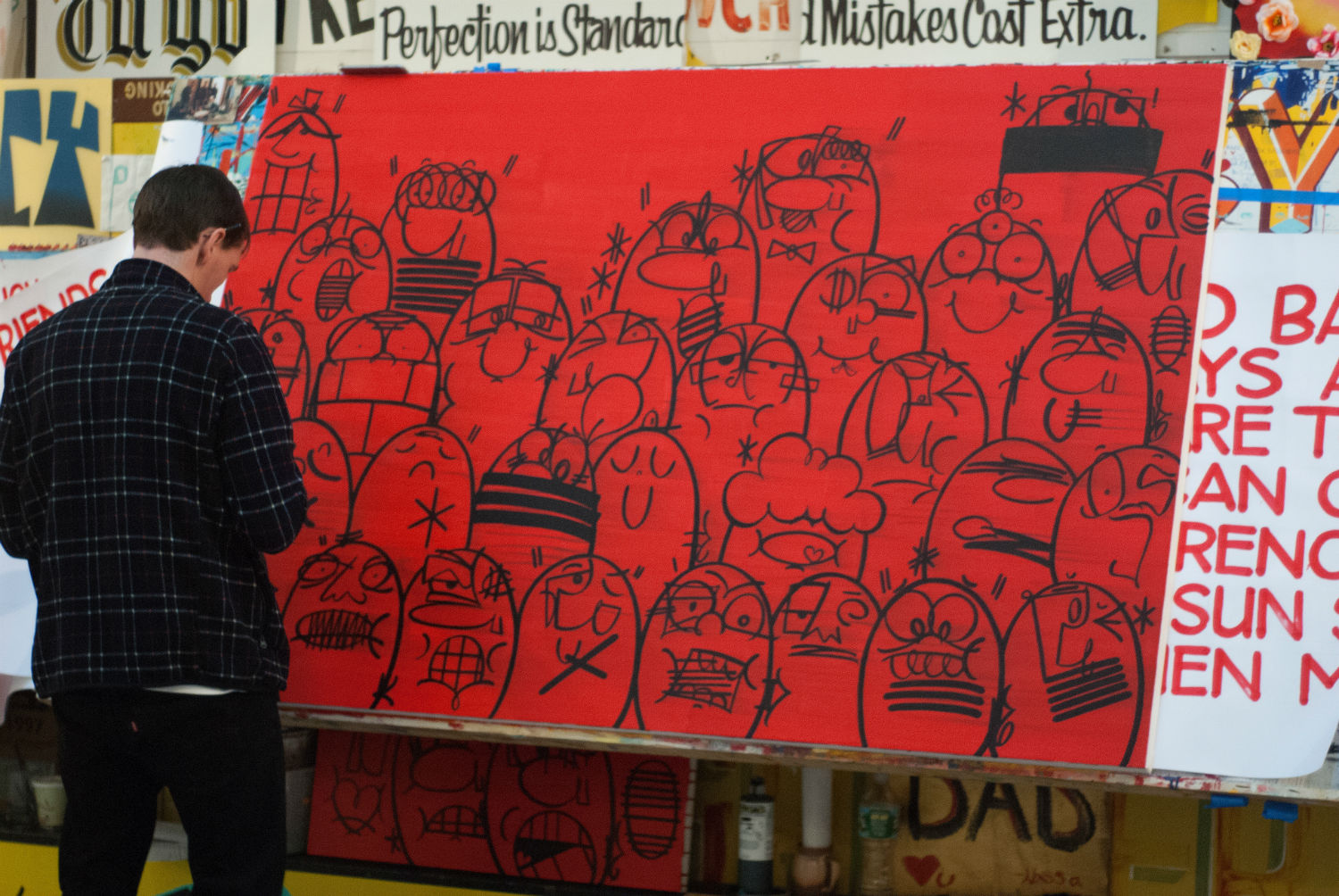

The key for me was studying art history just as hard as I studied graffiti history. I come from a world of street and of graf history, and always instilled in me was a sense of knowing where I come from within that. But I’ve also always known I was part of something bigger as an artist. Once I realized every pen stroke can turn into a brush stroke, and whatever I can draw on paper I can transfer into a painting, my ideas got much bigger. It went from tags to twenty-foot paintings.

Looking at all your line faces, there’s such an eclectic population of people.

They are portraits or masks that come from the line I developed through all the things I've learned through the years: tagging, calligraphy, art history, fighting, climbing, running, taking, giving, even other artists I've learned from and admire. It's all muscle memory and it's all included in these lines. They are the result of my history and I hope to learn how to use them properly to tell the story I want to tell. It’s really intense to capture so many emotions on one canvas. I’m trying to get them to be more human and relatable to an actual person, as opposed to being too cartoony or candy looking.

Now that you’re out, does is it affect the look of the characters? Are you meeting a more diverse range of people to draw?

Maybe. You’d be surprised. I wasn’t a disconnected derelict. The faces could be me on any given day. I mean, just yesterday I went from meeting with my P.O. to meeting with a V.P. at the Brooklyn Library, to going to a high school talent show where a teacher I worked with shouted me out to the students, who all turned around and looked at me. I was like, “Whoa.” It was a whole range of emotions, and my ups and downs of the day are in these faces. Some days I’m full of self-doubt, but when I can pay bills and send people money who are incarcerated, it helps me stay focused.

Did you ever think your work would become a means of currency?

I always hoped it would. I was determined it would be. I worked at a name brand clothing company called Miskeen when I was a teenager, all hand-painted clothing, and everyone was wearing it. All the rappers, Pharrell, it was in music videos. So I learned early on how to take paint and make money out of it, like silk screening and acrylics. And being from Philadelphia, we hate the Dallas Cowboys, so any time they came to town, I would make like a hundred “Fuck Dallas Cowboys” T-shirts with my silkscreen press to feed the frenzy. Me and my cousin would get on the train wearing the T-shirts, with a hockey bag full of the rest, and ride from Kensington to City Hall, and from City Hall, all the way to the stadium in South Philly. We would sell the shirts in the parking lot and tailgate parties. I don’t know what else it is, but selling Fuck Dallas Cowboys T-shirts on the train is definitely street art.

The hustle while incarcerated was portraiture, which is the number one moneymaker. The biggest hustle anywhere on the planet is being an artist, but even more in jail, specifically. I already had a name from working at Miskeen and being Agua, so once I realized in jail that portraits were worth the most money, the next step was to make them. I had a seven-year vacation, and in order to get everything I wanted, I learned quickly that it would be through portraits. Pastel and charcoal portraits.

What is it about making portraits specifically in prison that is so desirable?

The number one thing people get in prison are photographs from family, so they want to make portraits of that or themselves and send them back. I would take a family portrait and mash the guy in it. Everyone trapped on the island wants to send home a gift to a girlfriend or their kids. It’s a struggle to keep reminding them that you are thinking of them.

You and Steve Powers go way back obviously. How did you two know each other?

Steve was older and from my neighborhood, so he immediately was a role model. I’ve been in his life for like ninety percent of his art career. I knew Alex Baker from the ICA before he curated the original Street Market show in Philly, but I was at that show in 1999 and met Twist and Reas. I was really young. I wasn’t really capable of caring about anything Steve was doing. He was just my man, and on another level, I knew that he was crazy. And I was crazy, so it was a perfect combination of crazy. He really gave me the keys and a clue that there is something I can do. I had options, but I just wasn’t making art at that point. I was writing on walls on some graffiti world street shit.

Let’s talk about A Love Letter For You, the large mural project across the rooftops of the elevated train line in West Philly that was also name of the film. We changed the character’s name, but one storyline is loosely based on you. When we were starting the film, we were conscious of creating a message that spoke to the people of Philly. On the other hand, Steve was also trying to send you a personal message for when you got out. We didn’t get a chance to meet before shooting started, but did you know it was going to be based on you, or that it was even happening?

I think news gets to the prison faster than it gets to the next neighborhood over. Even though I’m a million miles away, I know what’s happening, plus I was in constant contact with Mike Levy and a bit with Steve too, so I knew about the movie. We can say it was originated as my story and what I was going through, but from a distance. It set a full circle to see that come to life for myself and a lot of people. Steve and I were always having conversations about getting back on those walls and painting those rooftops legally. While I was trying to pay court costs and fines, I knew he was going to figure that other part out, but I could never imagine that it was something on that scale. It brought all these great people working together, and a film came out of it. Some of my dear friends are in it. People who would never show their face on camera came and acted in it. Some of these guys never would have gotten involved with something like this. It doesn’t register for everyone from my neighborhood to get involved with an art project or film, especially about someone they grew up with.

When we finally did meet up at the Brooklyn Museum, you hadn’t seen the movie yet. What were your thoughts when you saw it, shortly afterwards?

I was dealing with too much. I just got done going through the exact experience the guy in the movie was going through, and I didn’t want it played back to me. It’s like I don’t want to come out and watch a cop show either. It was too early to take it in. I finally did watch it with Ari On The Go, who was also in the movie, and it was weird, like looking into a mirror of me or something.

So, while you are in prison, the film comes out, then you get out and wind up as one of the artists at the Brooklyn Museum’s Coney Island Is Still Dreamland (To A Seagull).

In the year leading up to my release, my conversations with Steve really switched, and he could tell I was onto something and meant it. Our conversations became business focused, and we built back and forth,

I said I was going to come home and make paintings, get involved with other projects and do the best I could at that. And I kept my word. Even when I was getting in trouble, I did the best I could at that. My motto is, “Never one day not having fun.” When Steve got the museum show, I knew I was in, I just had to get there.

I got out on Wednesday November 11th, and Thursday November 12th, I walked into the Brooklyn Museum and became part of the group exhibit on the fifth floor rotunda. There were tower frames being built and sign painting benches with easels so we could paint to the roof! A week later, we opened, and I was still readjusting. I was in culture shock. My eyes wouldn’t shut, they were so wide open.

What was cool about the exhibit was you and Steve were on display making paintings and signs while people could just walk past and observe. Did that affect you at all?

It was a shock. I could barely breathe. I had no clue what Steve was talking about. He said we would be in the museum painting. What started out to be a few days a week turned into almost every day. Hundreds of people watched us. I was always in great company. The museum guards, janitors, painters; they were the coolest. We blasted music. All types of people would attach themselves to me, spend some time and tell me their life story. I was immediately thrust into the spotlight, girls were talking to me finally, not vice versa, I even got an amazing girlfriend who works at the museum. I couldn’t have asked for a better homecoming.

Since the Coney Island show came down, what have you been doing?

I’ve been working with a school. Inner city high schools have money taken away from them to build more prisons. The conditions are way worse than my prison. They put money into prisons. Prisons are nice places. The grass is cut. It’s human warehousing, but they’re nice places. They’re building three new prisons in Philadelphia and shutting down, like, 56 schools. It’s mind boggling to me. Kids come in by the dozens by mistake.

I possessed a real strength as a graffiti writer in my time. I had the power. I had the tool for immediate mass communication. I didn’t ask for permission. I didn’t ask for forgiveness. I was able to communicate with as many people that I wanted to on any given night. Moving forward, it was important to never lose that power, but it’s a collaboration now. It seems like everything in my life has come out of the Brooklyn Museum. I met a guy there named Evan who teaches at the Clara Barton school in Brooklyn. It’s all poor kids, and it’s really run down. They feed kids breakfast, lunch, and dinner there. They have nothing going on really that’s creative, and they asked if I could paint a mural. We are doing workshops on how the detention class can be with me painting instead of sitting. I’m there to paint, but also to show them that they can use their creative powers to get in a better position in life. That’s what I’m trying to do. I have a year-long residency at the school there, going from wall to wall, showing them somebody cares.

What kind of reaction are you personally feeling toward your artwork now?

The work holds so much more meaning, and I try to see who I am and who I want to become. Seeing it large scale helps me figure myself out. Other people can look at it and see change and that they can change. It’s not just smiley faces. It’s someone who can turn a negative into a positive.

I can see how I want to move forward. Now I have my own studio and years and years of drawings that I can finally see in one place and connect the dots and put my thoughts together. I paint these faces now, but this is a short stay. This is a stepping-stone to the next level. I’m trying to get to where I’m having a dialogue with my paintings, where I can speak more to where I come from and also to where I’m coming from.

----

Originally published in the April 2017 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine, on newsstands worldwide and in our web store.